Sociolinguistic Approaches to Lexical Variation in English: Why Words Matter

We are pleased to announce publication of Sociolinguistic Approaches to Lexical Variation in English (Routledge), co-edited by Concept Analytic Lab’s own Rhys Sandow (with Natalie Braber, Nottingham Trent University). The volume serves to recognise the shift towards words as a unit of sociolinguistic study and provides contributions from many leading scholars in the field. The 17 chapters within the volume display the diversity of approaches in the sociolinguistic investigation of words and their meaning.

The goal was to create a collection that demonstrates the richness and complexity of lexical variation across English varieties worldwide. The chapters in this book explore how social factors, such as age, gender, and region, intersect with lexical choice, and how these choices reflect broader patterns of identity, ideology, and change. From youth language to specialised registers and emerging digital forms, the studies here reveal that vocabulary is not just a passive repository of words but an active site of sociolinguistic meaning-making.

The volume is organized around three key themes. The first section focuses on dialectology. Many of the chapters within showcase how big data, such as those collected from large-scale surveys or social media, can better help us to understand the mechanisms of language variation and change. These chapters highlight the dynamic interplay between local norms and global influences, offering insights into processes of lexical diffusion and retention.

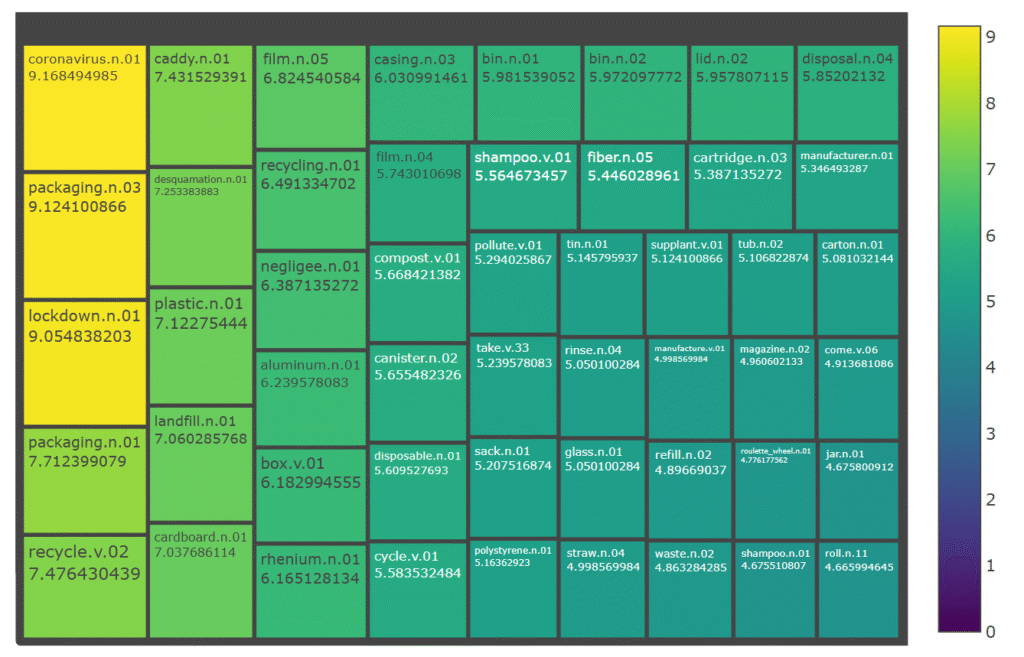

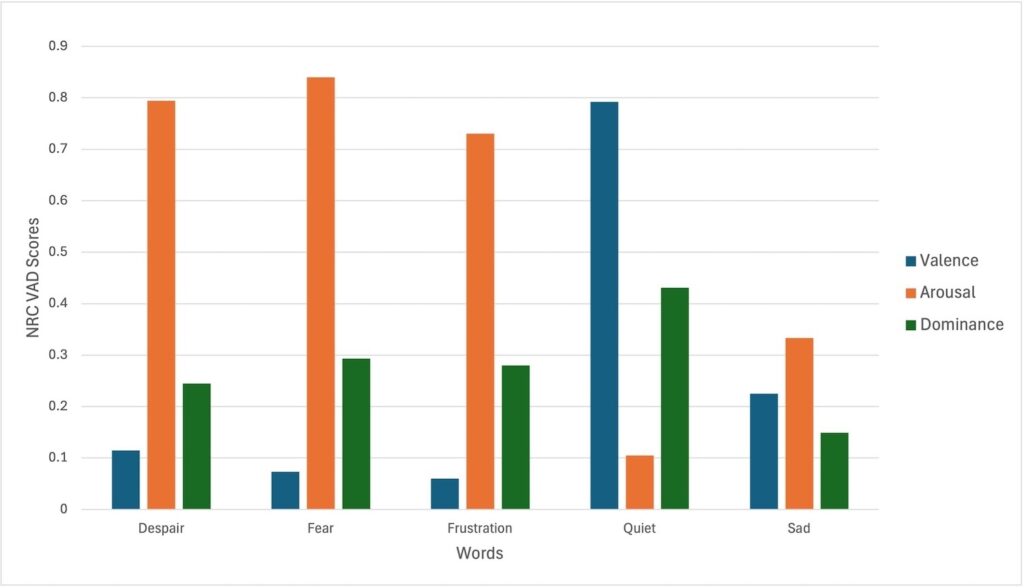

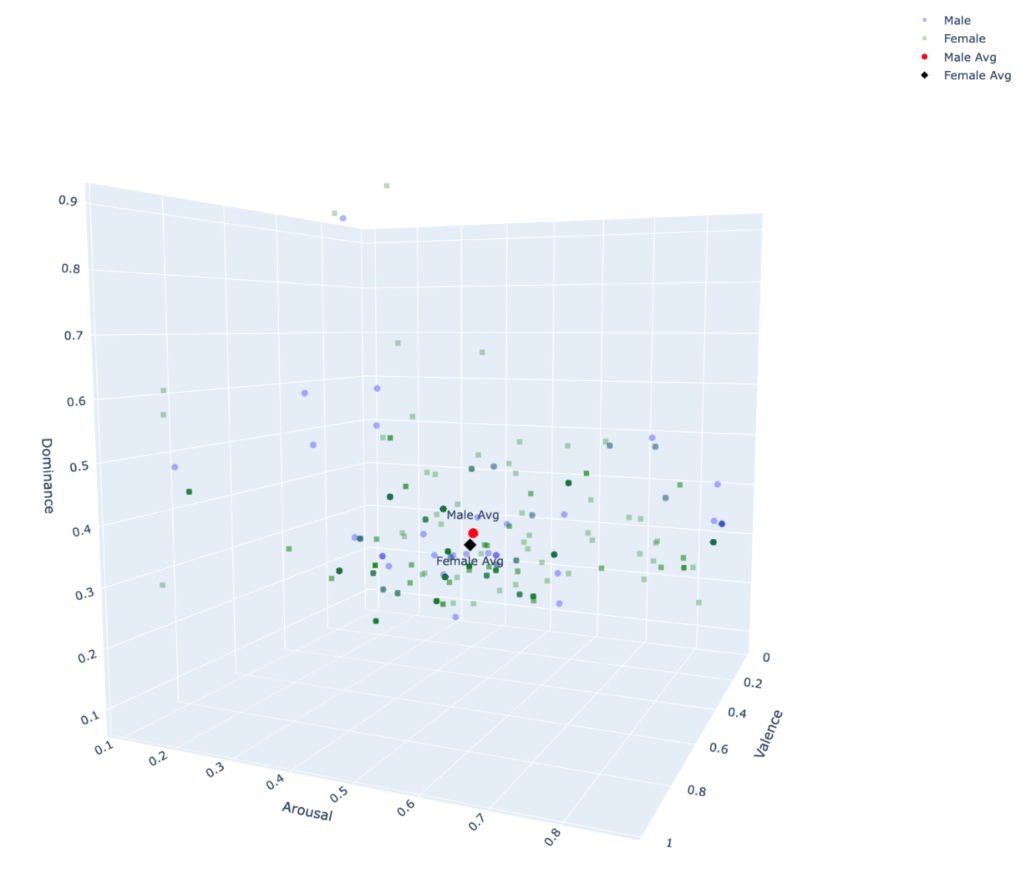

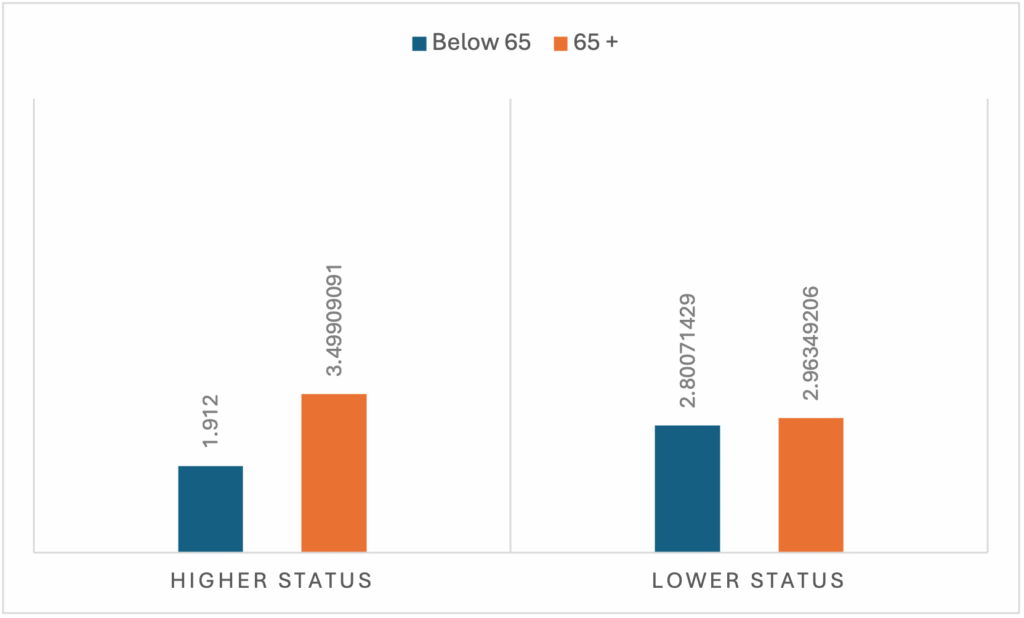

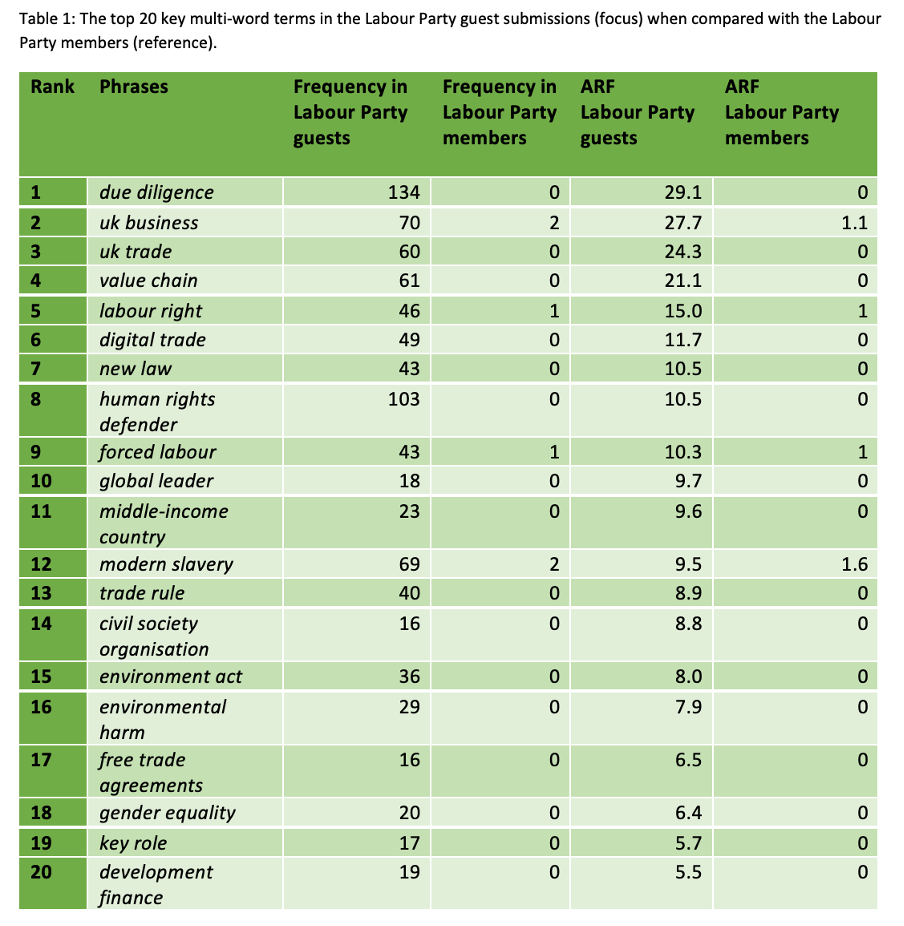

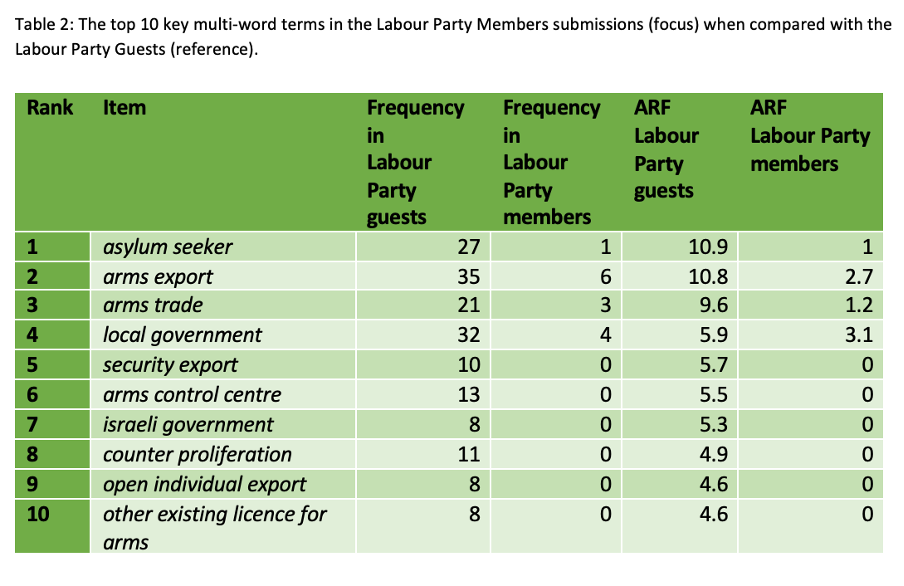

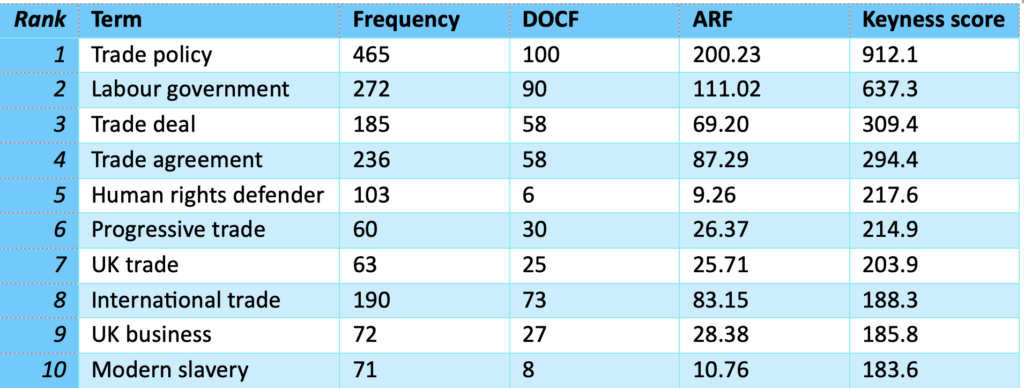

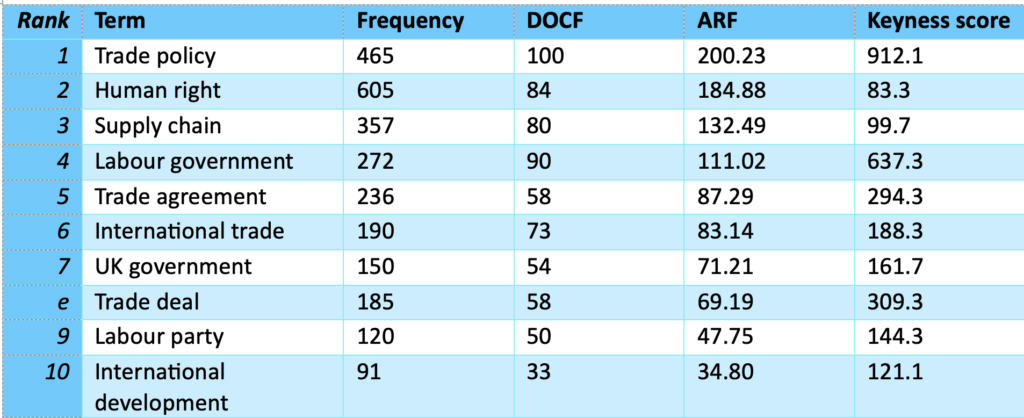

The second section, on corpus linguistics, highlights the way in which computational tools can be used to extract meaning from large volumes of texts. In this section, Concept Analytics Lab’s researchers (Justyna Robinson, Rhys Sandow, and Albertus Andito) showcase our very own Concept Cruncher tool in the context of gendered variation (see our blog on this chapter here). The contributions in this section particularly resonate with CAL’s mission to use corpus techniques to transform large text data into impact, in academic, political/policy, and commercial spheres.

The third section is concerned with social meaning, from both experimental and ethnographic perspectives. In this section, CAL’s Rhys Sandow (with Christian Ilbury, George Bailey, and Natalie Braber) combine experimental and ethnographic methodologies to investigate the social meaning of the Multicultural London English quantifier bare‘lots of’ (as in, ‘there are bare people at the party)’. These contributions push the boundaries of how sociolinguists study vocabulary and enable us to better understand the social life of words and their role in identity construction and social distinction (à la Bourdieu).

The chapters within the volume address the implications of lexical variation for sociolinguistic models. By foregrounding lexis, the contributors challenge us to rethink assumptions about linguistic structure and change. What does it mean for variationist theory when vocabulary, not just sounds or grammar, becomes central to our understanding of language variation? The chapters offer diverse perspectives on this question, sparking dialogue that we hope will resonate across the field.

This collection has been years in the making, and it reflects the collaborative spirit of sociolinguistics at its best. Each chapter brings a unique lens to the study of lexical variation, yet together they form a coherent narrative: that words matter, and that studying them can transform how we understand language and society.

Whether you’re a researcher, student, or simply curious about the social life of words, we invite you to dive in, explore the chapters, and join the conversation about how we can push the frontiers of knowledge and impact through the sociolinguistic study of words and meaning.

About Us

We identify conceptual patterns and change in human thought through a combination of distant text reading and corpus linguistics techniques.