Angelou, Angelos., Stella Ladi, Dimitra Panagiotatou, & Vasiliki Tsagkroni. 2023. Paths to trust: Explaining citizens’ trust to experts and evidence-informed policymaking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration, Advance Online Publication.

Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), 216-224.

Biber, Douglas. 2006. Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 5, 97–116.

Cairney, Paul. & Adam Wellstead. 2021. Covid-19: Effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians and the public. Policy Design and Practice, 4 (1), 1–14.

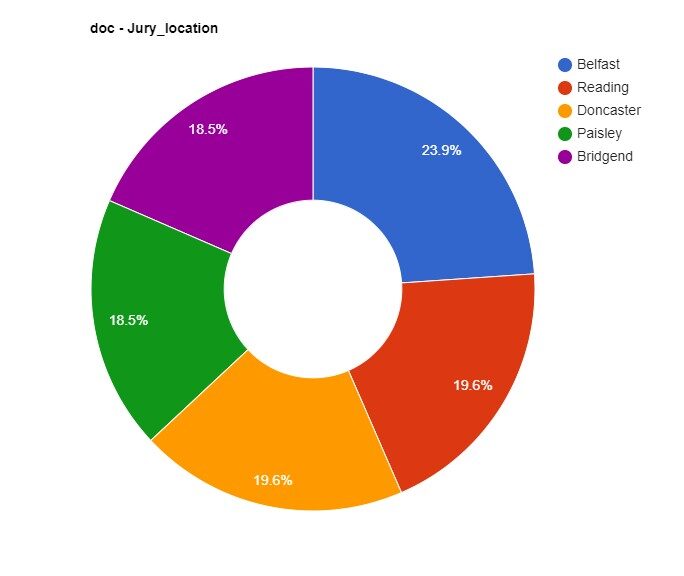

CITP (2023) Research into public attitudes to trade, CITP, University of Sussex, https://citp.ac.uk/public-attitudes-to-trade

Clements, Michael and Laura King 2023. Trust in politicians reaches its lowest score in 40 years, IPSOS, 14th December 2023, https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/ipsos-trust-in-professions-veracity-index-2023

Dommett, Katharine. & Warren Pearce. 2019. What do we know about public attitudes towards experts? Reviewing survey data in the United Kingdom and European Union. Public Understanding of Science, 28 (6), 669-678.

Du Bois, John W. 2007. The stance triangle. In Robert Englebretson (Ed.), Stancetaking in Discourse, 139–182. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Eckert, Penelope. 2019. The limits of social meaning: Social indexicality, variation, and the cline of interiority. Language, 95 (4), 751–776.

Gauthier, David. 1987. Morals by Agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henig, David and L Alan Winters (2024). ‘Restructuring the Board of Trade for the Twenty-first Century’. Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy Working Paper 014, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/restructuring-the-board-of-trade-for-the-twenty-first-century

Hestermeyer, Holger and Alex Horne. 2024. Treaty Scrutiny: The Role of Parliament in UK Trade Agreements, Briefing Paper 9, Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/treaty-scrutiny-the-role-of-parliament-in-uk-trade-agreements

Jaffe, Alexandra. (Ed.). 2009. Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kiesling, Scott F. 2009. Style as stance. In Alexandra Jaffe (Ed.), Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, 171–194. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kiesling, Scott F. 2022. Stance and stancetaking. Annual Review of Linguistics, 8, 409-426.

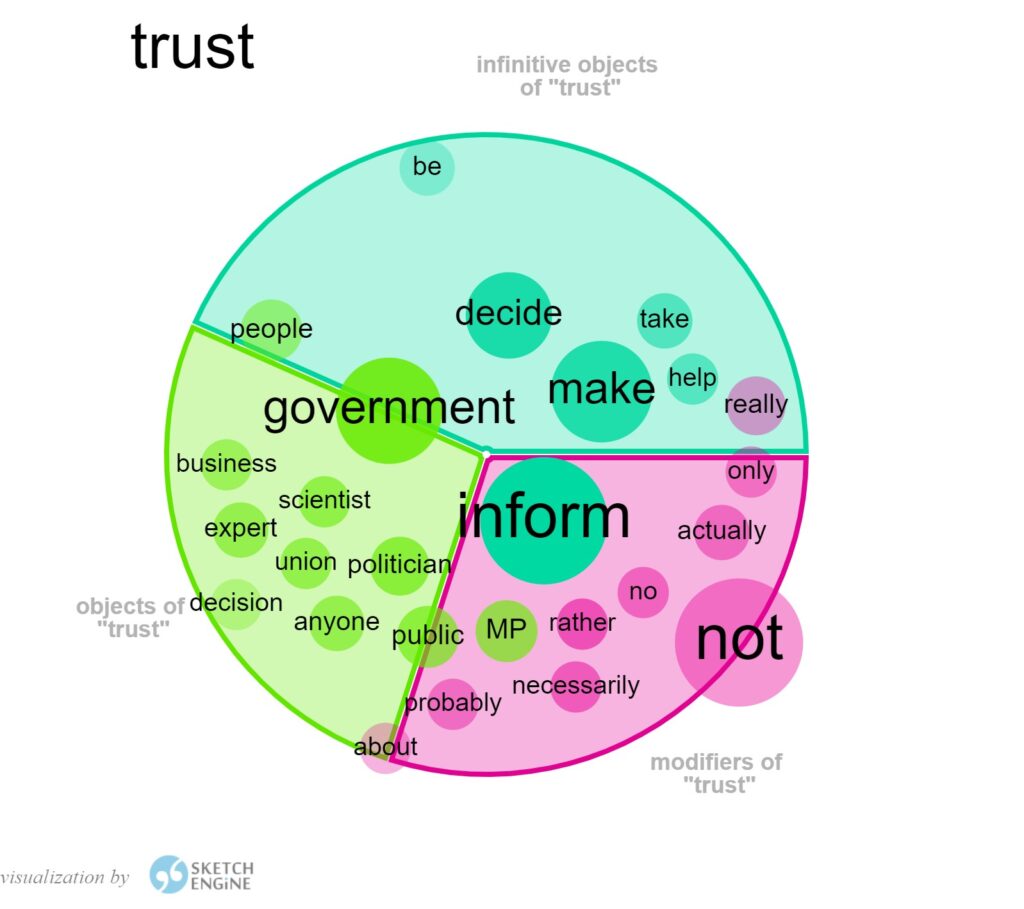

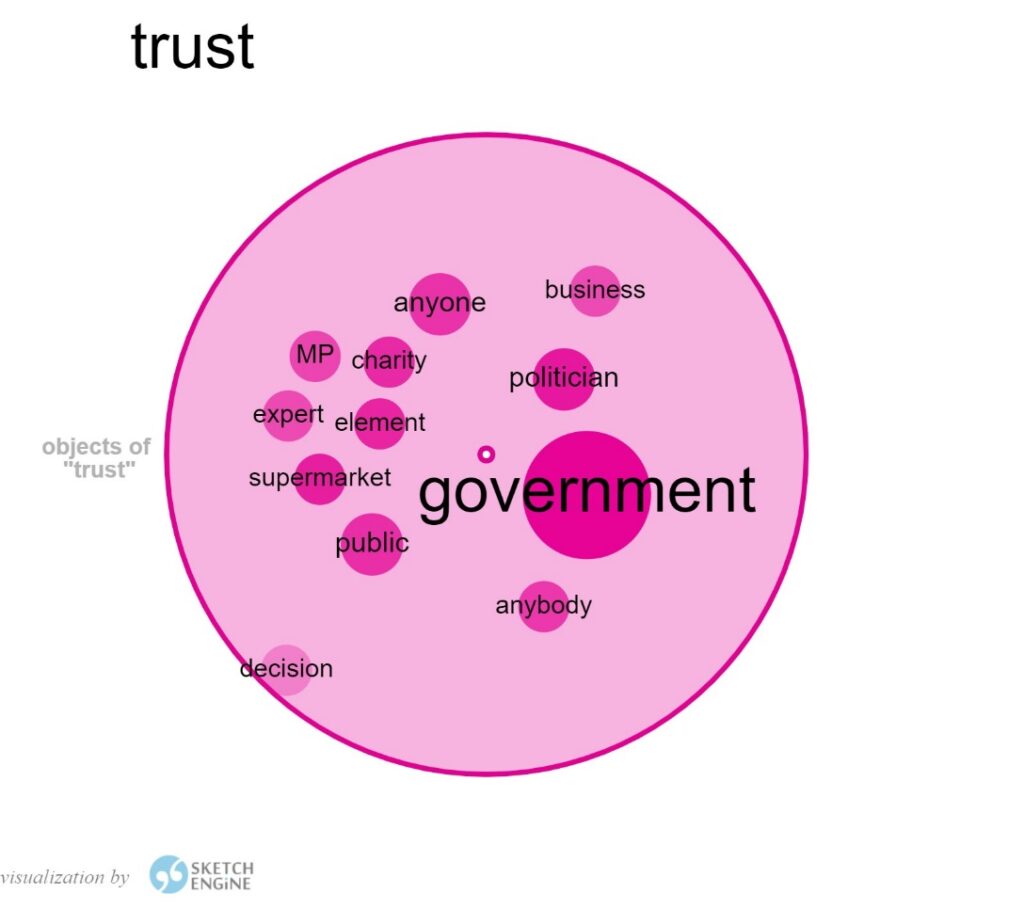

Kilgarriff, Adam., Pavel Rychlý, Pavel Smrž, David Tugwell. 2004. The Sketch Engine. Proceedings of the 11th EURALEX International Congress, 105-116.

Kilgarriff, Adam., Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý, and Vít Suchomel. 2014. The Sketch Engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1: 7-36.

Litva, Andrea., Joanna Coast, Jenny Donovan, John Eyles, Michael Shepherd, Jo Tacchi, Julia Abelson, Kieran Morgan. 2002. ‘The public is too subjective’: public involvement at different levels of health-care decision making. Soc Sci Med, 54(12), 1825-37.

Love, Robbie., Claire Dembry, Andrew Hardie, Vaclav Brezina, & Tony McEnery. 2017. The Spoken BNC2014: Designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22(3), 319-344.

Locke, John. 1960. Two Treatises of Government. Ed. Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Partington, Alan. 2004. Corpora and discourse: A most congruous beast. In Alan Partington, John Morley, and Louann Haarman (eds.), Corpora and Discourse, Bern: Peter Lang, 9-18.

Petetin, Ludivine., Charles Whitmore, and Aileen Burmeister (2023) ‘Addressing barriers for Welsh institutions and civil society to contribute to UK trade policy’, CITP Briefing Paper 6, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/addressing-barriers-for-welsh-institutions-and-civil-society-to-contribute-to-uk-trade-policy

Winsvold, Marte., Atle Haugsgjerd, Jo Sagile, & Signe Bock Segaard. 2024. What makes people trust or distrust politicians? Insights from open-ended survey questions. West European Politics, 47 (4),759–783.

Winters, L. Alan (2020) ‘Brexit and Covid: Experts – who needs ‘em?’, The UK in a Changing Europe, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexit-and-covid-experts-who-needs-em/

Winters, L Alan (2024) ‘How do we make trade policy in Britain? How should we?’ Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy Working Paper 011, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/how-do-we-make-trade-policy-in-britain-how-should-we