The Labour Party’s 2024 Manifesto - The Voice of Members or Lobbyists?

by Justyna A. Robinson and Rhys Sandow

CAL Briefing Paper 1

published online on 3rd July 2024

The Labour party has been criticised recently for the volume of its candidates in the 2024 general election with backgrounds in lobbying [1,2,3]. Indeed, this led Novara Media (2024) to question whether the Labour Party is ‘The Lobbyists’ Party’ [4, also 5]. In this article, we assess this claim by considering extent to which the Labour Party’s 2024 general election manifesto is consistent with either the desires of party members or of lobby groups, as articulated in the Labour party’s 2023 National Policy Forum Consultation on progressive trade policy [6].

While Labour’s 2023 National Policy Forum (hereafter, NPF) considered a variety of policy areas, our focus here is its forum on trade. Excluding duplicates, there are 302 submissions to the consultation, with 109 submitted by guests (i.e. business and other lobby interest groups), 187 by Labour Party members and the rest by National Policy Forum representatives. In total, there are 244,894 words submitted to the forum. While the majority of submitters were Labour Party members, they produce a minority of the total word count, with 24.7% of words produced by members, as opposed to 71.2% by guests (the rest by NPF representatives). For a more detailed take in the data see Gasiorek et al (2024) [7].

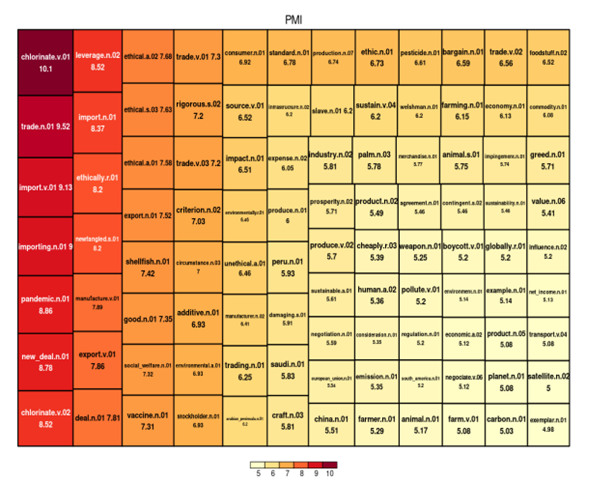

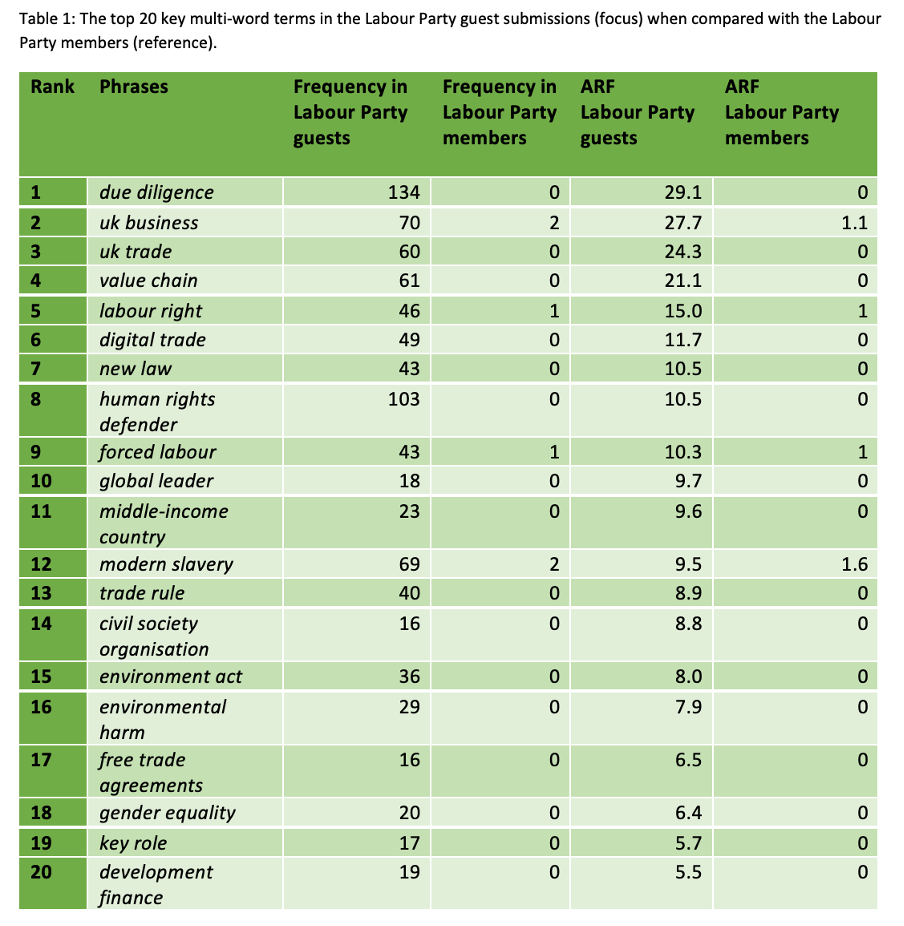

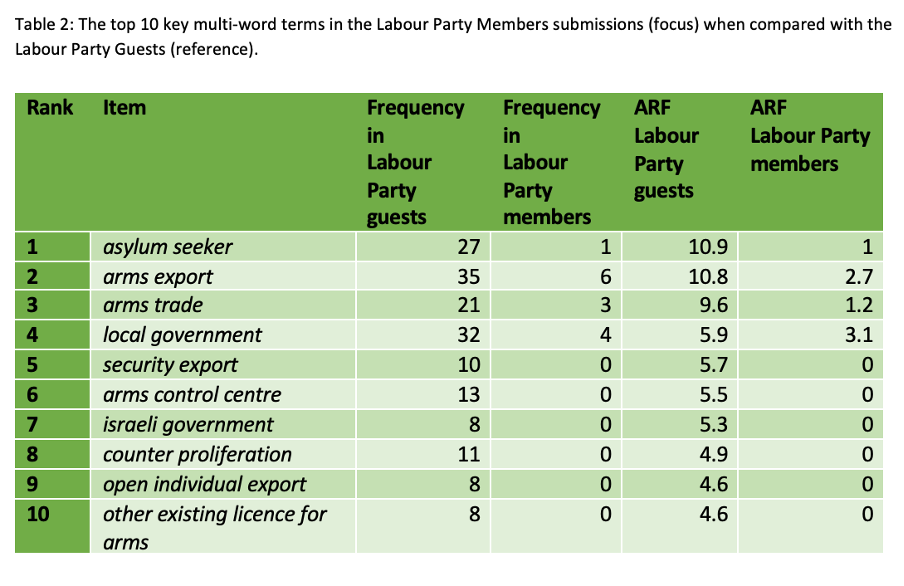

We contrast the top multi-word terms (i.e. phrases) that are used disproportionately by Labour Party guests versus and Labour Party members (see Table 1), and vice versa (Table 2) [8]. Note that the results are ordered by ARF (Average Reduced Frequency) which is a modified frequency measure that accounts for distribution across the submissions, so that one response does not skew the results, see Sandow & Robinson (2024) [9]).

Table 1 shows that relative to members, guests are more concerned with the mechanisms and process of trade, as highlighted by phrases such as supply chain, due diligence, value chain, and new law. The guests are also more concerned with environmental issues, such as environment act and environmental harm. Additionally, guests focus on human rights, which is a theme represented by phrases such as human rights defender, forced labour, modern slavery, and gender equality.

So, does the Labour Party Manifesto address these considerations?

The Labour Party Manifesto [9] identifies the need for resilient supply chains (resilient supply chains is in the wording of one of the questions in the NPF), as expressed with the following:

“We will ensure a strong defence sector and resilient supply chains, including steel, across the whole of the UK.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

The environment is a key theme in the Manifesto, with energy and climate occurring 68 and 24 times, respectively. In particular, the ways in which trade agreements can be a vehicle for pursuing a green agenda is recognised in the Manifesto in the following way:

“We will seek a new strategic partnership with India, including a free trade agreement, as well as deepening co-operation in areas like security, education, technology and climate change.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

Human rights, including gender equality, are also mentioned throughout the Manifesto, although not discussed directly in the context of trade.

“We will use the UK’s unique position in NATO, the UN, G7, G20, and the Commonwealth to address the threats we face, and to uphold human rights and international law.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

“Labour will take action to reduce the gender pay gap, building on the legacy of Barbara Castle’s Equal Pay Act.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

The Manifesto does not mention due diligence, although it is reasonable to assume that this is implicit under the umbrella of good practice and does not mention any new laws in relation to trade, although they do commit to other new laws, e.g. ‘Martyn’s Law to strengthen security of public events.

Now, turning the attention to the submissions by the Labour party members. Table 2 shows the phrases that are used disproportionately by Labour Party members, relative to guests.

Note, due to the lower quantities of text produced by Party members, here we present the top ten phrases (Table 2), as opposed to the top twenty phrases for the Party guests presented in Table 1.

Party members are more likely to discuss arms which is evident via their use of phrases such as, arms export, arms trade, counter proliferation, including, but not limited to, the Israeli government. They are also more likely to discuss local government and asylum seekers. In context, these phrases typically reference a desire for greater regulation and moral consideration on those with whom we trade arms, greater power for local governments, and a more welcoming environment for asylum seekers.

In terms of the theme of arms, the Manifesto makes a commitment to upholding international law, but avoids references any specific nation or any specific commitments beyond that:

“Labour will support industry to benefit from export opportunities in line with a robust arms export regime committed to upholding international law.” (2024 Labour manifesto)

While the Manifesto does not mention Israel/Palestine in relation to arms exports, they do address this elsewhere:

“Long-term peace and security in the Middle East will be an immediate focus. Labour will continue to pish for an immediate ceasefire, the release of all hostages, the upholding of international law, and a rapid increase of aid into Gaza. Palestinian statehood is the inalienable right of the Palestinian people. It is not in the gift of any neighbour and is also essential to the long-term security of Israel. We are committed to recognising a Palestinian state as a contribution to a renewed peace process which results in a two-state solution with a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable and sovereign Palestinian state.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

There are multiple commitments in the Manifesto to provide greater autonomy for local and devolved governments, such as:

“Local government is facing acute financial challenges because of the Conservatives’ economic mismanagement which sent interest rates soaring, along with their failures on public services. To provide greater stability, a Labour government will give council multi-year funding settlements and end wasteful competitive bidding.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

Lastly, while both the Party members’ responses to the NPF and the Manifesto discuss asylum seekers, the framing of asylum seekers differs in each context. In the NPF, members implore the Labour Party to provide greater support for asylum seekers:

“We must promote Labour values by treating refugees and asylum seekers with dignity and respect. This means providing a safe, legal route for refugees and ending detention in camps while claims are being processed. Asylum claims must be processed more quickly and people should be permitted to work while their claims are being processed.” (response to the 2023 Labour National Policy Forum Consultation on progressive trade)

Whereas, in the Manifesto, asylum seekers are discussed in the context of perceived Conservative failures:

“Rather than a serious plan to confront the crisis, the Conservatives have offered nothing but desperate gimmicks. Their flagship policy- to fly a tiny number of asylum seekers to Rwanda- has already cost hundreds of millions of pounds. Even if it got off the ground, this scheme can only address fewer than one per cent of the asylum seekers arriving.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

Or in the context of returning failed asylum seekers to safe countries:

“We will negotiate returns arrangements to speed up returns and increase the number of safe countries that failed asylum seekers can swiftly be sent back to.” (2024 Labour Manifesto)

To conclude, the Labour Party Manifesto speaks to both the concerns of both lobbyists and Party members, as well as where they intersect, for example by aligning more closely with the EU. However, the concerns highlighted in the forum are not always addressed directly in relation to trade, but in broader policy commitments. Also, the ways in which these topics were addressed were not always consistent between the Forum and Manifesto. For example, while NPF responses advocated greater dignity and respect for asylum seekers, this was not explicit in the Manifesto. Ultimately, by and large, the Manifesto does not demonstrate a bias towards lobbyists, but manages to find an equilibrium between the desires of two distinct, yet critically important, groups.

References

[1] https://novaramedia.com/2024/06/13/meet-the-labour-candidates-lobbying-for-oil-gas-and-arms-companies/ . Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[2] Concern over ‘corrosive’ impact of Labour candidate working as lobbyist. The National. https://www.thenational.scot/news/24205441.concern-corrosive-impact-labour-candidate-working-lobbyis/. Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[3] Labour’s corporate lobbying links with Polly Smythe. Macrodose Election Economics. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6UmKWzzXx8XwU1Q8iPKH3A . Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[4] Novara Media @novaramedia. (2024). (video). Tik Tok. https://www.tiktok.com/@novaramedia/video/7382148715156376865?lang=en . Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[5] The Labour Party becomes the Lobbyists Party. Morning Star. The Labour Party becomes the Lobbyists Party | Morning Star (morningstaronline.co.uk) . Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[6] National Policy Forum Consultation (2023) Available via https://policyforum.labour.org.uk/commissions. Accessed 13th June 2024.

[7] Gasiorek, Michael, Justyna A. Robinson, and Rhys Sandow (2024) Labour’s Progressive Trade Policy: Consultations and policy formulation. UKTPO Briefing Paper 81 – June 2024. Available via https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/publications/labours-progressive-trade-policy-consultations-and-policy-formulation/ Accessed 3rd July 2024.

[8] The analysis is done via SketchEngine. Available via http://www.sketchengine.eu/

[9] Sandow, Rhys and Justyna A. Robinson (2024) How can you identify key content from surveys? Concept Analytics Lab Blog. Available via https://conceptanalytics.org.uk/identifying-key-content-from-surveys/ Accessed 13th June 2024.

[10] Labour Party Manifesto. (2024). Available via https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Labour-Party-manifesto-2024.pdf. Accessed 13th June 2024.

About Us

We identify conceptual patterns and change in human thought through a combination of distant text reading and corpus linguistics techniques.