How language reveals different faces of loneliness

by Justyna A. Robinson, Gayathri Sooraj, and Caitlin Hogan

The World Health Organisation has introduced a commission on social isolation (see here). This is a response to what many commentators (e.g. here and here) have declared an epidemic of loneliness. We have understanding of the scale of loneliness and that nearly half of adults in the UK feel lonely occasionally, sometimes, often, or always (see here). Some groups are especially at risk of loneliness, particularly young, disabled people (see here). However, we know less about how people describe loneliness or what linguistic features are associated with discourses of loneliness (see here). These questions were explored by Justyna Robinson (Concepts Analytics Lab) and Faith Matcham (Psychology) at the University of Sussex , whose work towards creating a personalised chatbot for loneliness intervention was funded by Sussex Digital Humanities Lab. Ultimately, our headline findings are that

- Loneliness is generally experienced with similar intensity across demographic groups.

- But the risk factors differ greatly, particularly according to age.

- Social media is discussed as a catalyst for loneliness for younger people.

- Outright social isolation is framed as a more pressing issue for older people.

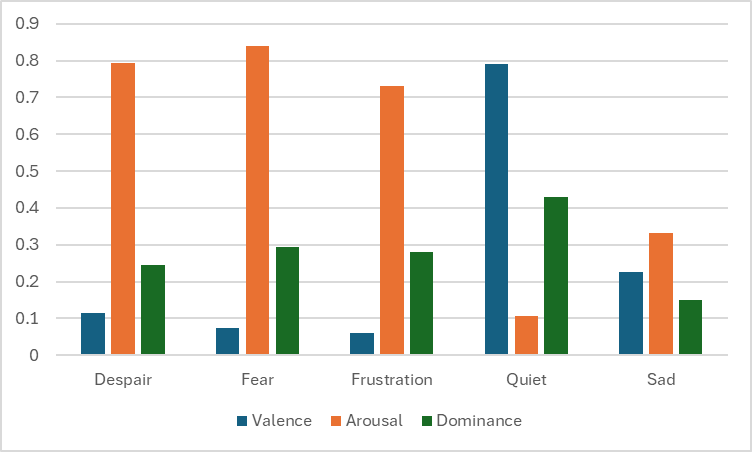

For this project we explored data on loneliness collected by Mass Observation Project (MOP). In 2019 MOP issued a survey, the directive on Loneliness and Belonging (see here). The directive consisted of two parts. Firstly, participants were asked to provide five words that they associate with loneliness, e.g. despair, fear, frustration, quiet, and sad (see Figure 1). Secondly, they provided long-form narrative responses to a series of questions related to the broader topic of loneliness.

Loneliness in five words

70 Writers shared the five words they associate with loneliness. These words expressed various aspects of affective meaning which we measured by

adopting Mohammned’s (see here) classification of valence, arousal, and dominance. Each of five words are assigned with a numerical value, from 0 to 1, for each of the three dimensions depending on how strongly they represent a given dimension.

- Valence refers to the positive (higher score) or negative (lower score) feelings associated with each word.

- Arousal relates to the intensity of the emotion, with higher scores reflecting greater intensity.

- Dominance refers to the degree of control exerted by a stimulus, with higher scores corresponding to greater control. To exemplify this, Figure 1 presents the words provided by a younger female of low socioeconomic status, alongside their scores across the three dimensions.

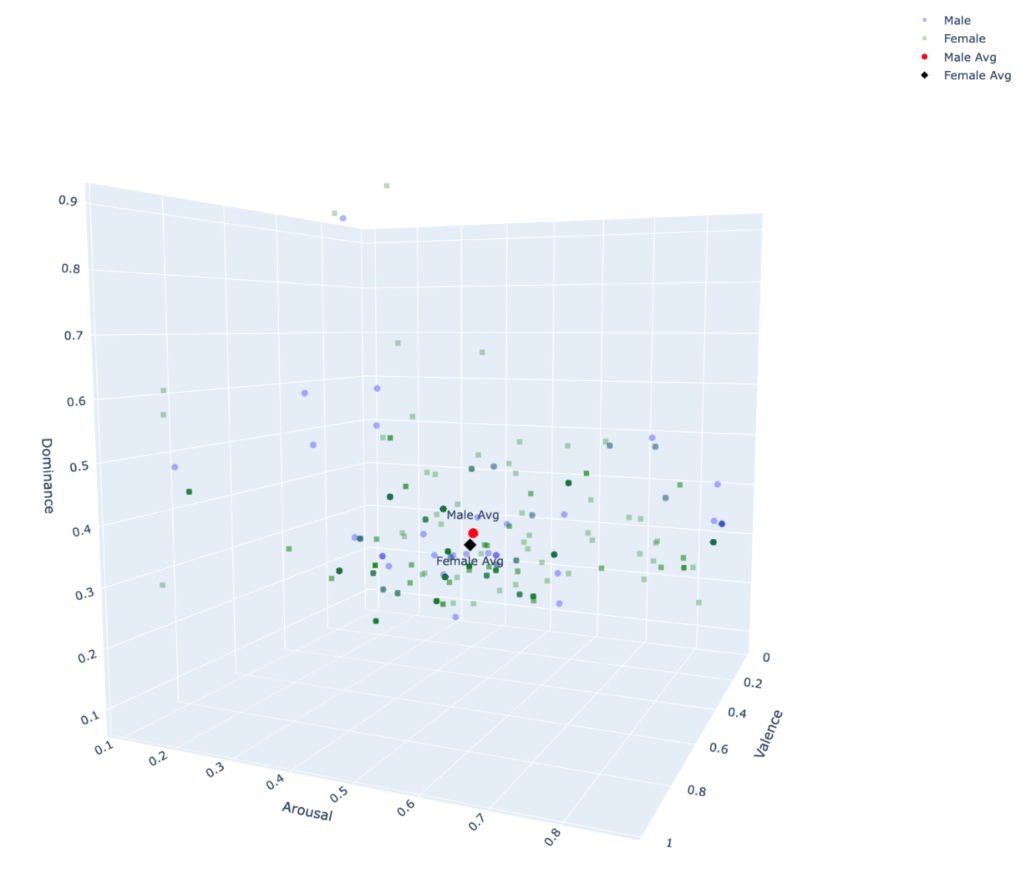

Findings highlight remarkable consistency across demographic groups in their conceptualisation of loneliness across the dimensions of valence, arousal, and dominance. Figure 2 highlights that the average results for male and female respondents are almost identical.

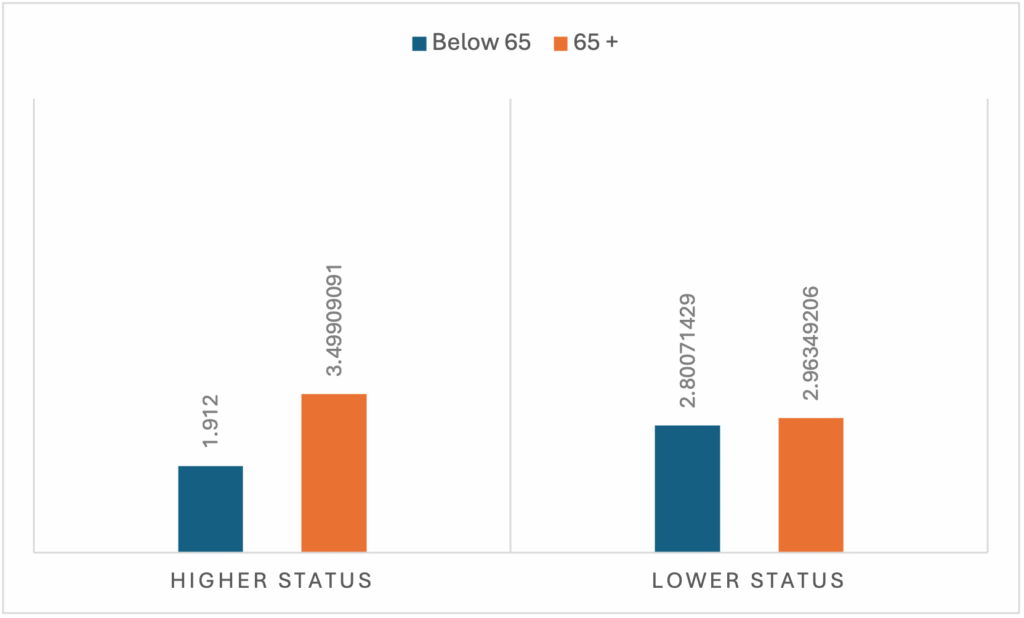

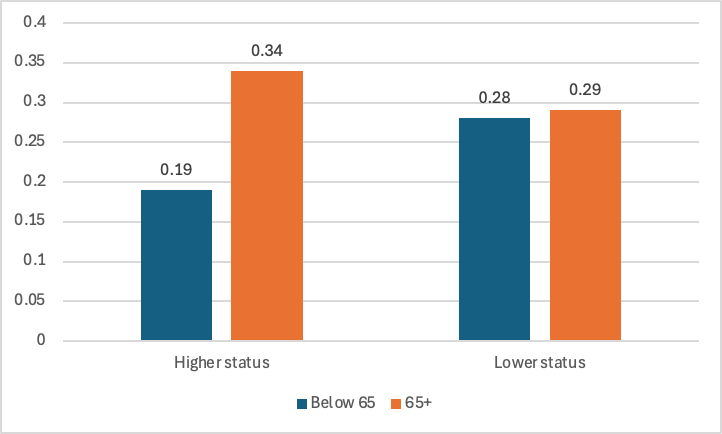

Indeed, statistical analysis identified very few meaningful differences in the data set. This speaks to a remarkable homogeneity in the conceptualisation of loneliness. The one exception to this was that on the dominance dimension there was an interaction between age and socioeconomic status. While age exhibited minimal differences among those in the lower status socioeconomic group, there was a much greater difference in the higher status group (see Figure 3). We consider age as a binary category for the purposes of this analysis, distinguishing between those who qualified for the state pension at the time of data collection (the state pension age was 65 in 2019) and those who did not.

Figure 3 shows that the effect of age on the experience of loneliness is much greater among higher status respondents, with those who are older in this category conceptualising loneliness as something that exerts a greater degree of control, relative to their younger counterparts. In particular, there is a large difference between status among younger respondents, with those of lower status conceptualising loneliness as exerting greater dominance than their higher status counterparts.

Loneliness in long-form narratives

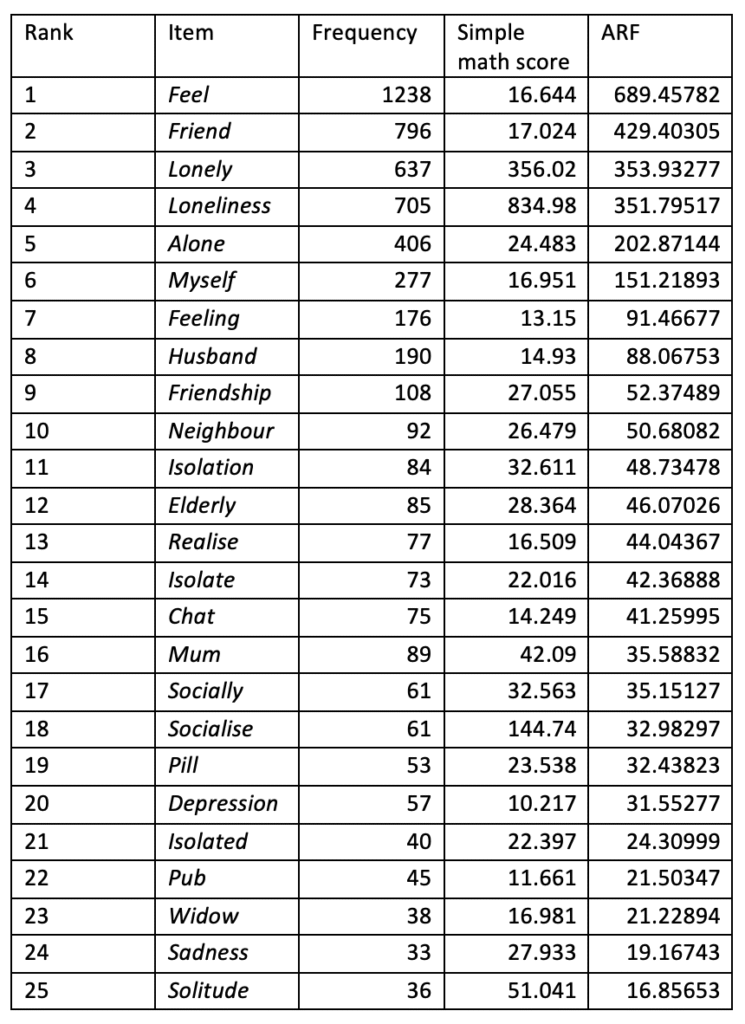

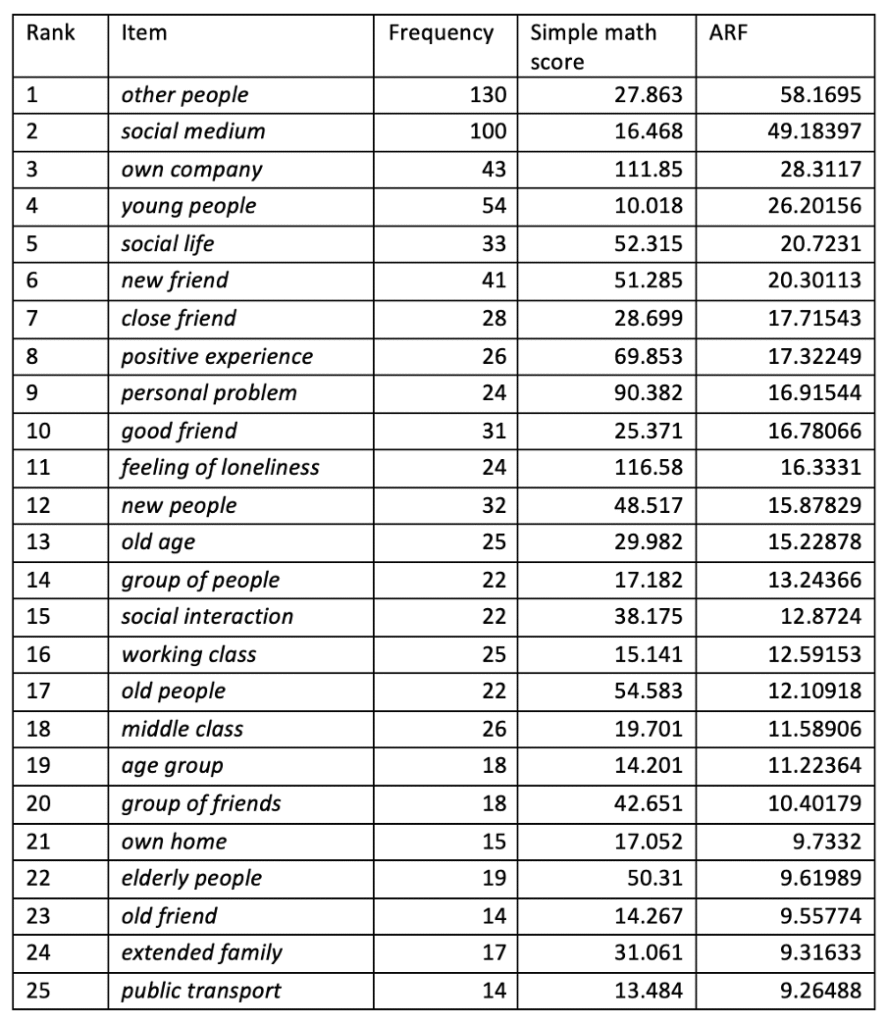

The longer, narrative responses to the directive discussed experiences of loneliness both on a personal level and at a broader societal level as well as speculation as to the causes of loneliness as well as potential solutions. . In order to understand the ‘aboutness’ of the data we look at key terms.

While a full analysis of these results is far beyond the scope of the blog here we consider one case-study, that of age.

Many of the key terms in Table 2 relate to the theme of age, e.g. young people, old age, old people, and elderly people. We have seen from the quantitative analysis of the affective meaning of the valence, arousal, and dominance that there was very little difference between age groups in the conceptualisation of loneliness (save for the interaction between socioeconomic status and age for the dominance scores). However, the longer-form responses highlight something else.

While both younger and older people are mentioned in the contexts of loneliness, the risk factors associated with these groups differ. Indeed, the discourses in which mentions of these groups appear highlight that the challenges relating to loneliness are not uniform. For example, social media was often mentioned in the context of young people:

- In the news it is reported that loneliness is on the increase, particularly amongst young people. This surprises me as young people are constantly communicating with others on social media. However, perhaps seeing what looks like a perfect life on someone’s Facebook account serves to exacerbate feelings of dissatisfaction and loneliness in people whose lives are not running smoothly.

- I understand that social media can cause young people to feel lonely and that other people are living a more interesting life. Unfortunately, it is full of lies but people don’t really understand that.

In contrast, discussions of older people’s loneliness were often framed in terms of isolation in more absolute terms, e.g.:

- I know that there are old people today who feel lonely. Particularly following the death of their spouse.

- Inevitably, as people live longer and stay in their own homes, isolation can become a serious problem. I believe the older generation can suffer considerably in this respect, particularly in rural communities where the shop and pub are now closed, the bus service has been withdrawn and children have grown up and live elsewhere.

Ultimately, using a suite of analytical tools, from sentiment analysis, to keyword analysis, to discourse analysis, enables one to garner insight into the conceptualisation of loneliness that is often missed in survey-type data. The discursive nature of this data enables lived-experiences of loneliness and its perceived risk factors to be unpacked in detail- the sort of detail that computational linguistic methods can cut through, to pick out key patterns and affective meanings. Ultimately, the findings from this report will inform the development of a chatbot that will serve as a tool to combat the loneliness crisis.

If you are interested in working with Concept Analytics Lab, please do contact us at Justyna.Robinson@sussex.ac.uk

About Us

We identify conceptual patterns and change in human thought through a combination of distant text reading and corpus linguistics techniques.