‘We’re saying that we trust them but really we don’t’: The discursive framing of TRUST in international trade deals

by Justyna A. Robinson, L. Alan Winters, Rhys Sandow, Sandra Young, Caitlin Hogan

Abstract

1. Introduction

International trade is a major issue for the British economy. About a quarter of the UK’s demand for goods and services is met from imports and about a quarter of the demand for UK production of goods and services comes from exports. About 6.5 million jobs depend on exports. While the UK was a member of the European Union or its precursors, policy on international trade was determined in Brussels with a little input from the UK and other member governments. Brexit brought full responsibility for UK trade policy back home to a government ill-equipped to discharge it, not least because it had little idea about attitudes to trade among the public.

In the years shortly after Brexit came into effect (2021) the UK had rolled over 30 trade agreements that it had been party to under the EU, agreed new terms for trade with the EU and signed new agreements with, Australia and New Zealand and with the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) with 11 Pacific nations. The 30 roll-overs (imperfectly) preserved the trading conditions the UK had under the EU, the agreement with the EU offered vastly inferior trading conditions to those which it had as a member, and official estimates suggested that the economic benefits of the new trade agreements were trivial – see Winters (2024).

The chosen instrument was a series of five Citizens’ Juries in which small groups were informed about, discussed and in some cases made mock decisions about trade policy questions. The recordings of these juries’ final discussions provide the raw material for this analysis, in which we look specifically at the questions of whom the public trusts to inform decisions and whom they trust to make them. A few more details are provided in Section 2 and a good deal more in the documents at CITP (2023).

- CJs place very limited trust in political actors

- CJs recognise that trust is critical to political processes

- CJs feel that there is a lack of options in who to trust

- CJs express a relatively high degree of trust in experts

- CJs’ opinion on trusting the public is divided

- CJs make a distinction between actors they trust to inform and to decide on trade deals

In Section 2 we discuss corpus-assisted discourse analysis as a method of analysing CJ conversations. In Section 3 we present findings which start with an observation that jurors place very limited trust overall in the process of decision-making with regards to trade deals. We then report on the relatively high levels of trust CJs afford to experts, and the limited trust they confer on the public. Specifically, we note the distinction that CJs made between informing the decision-making process and actually making decisions regarding trade policy.

2. Method

Each jury was of around 20 people (with no attrition – perhaps because jurors were remunerated) and representative of its local area. Each met five times: four times virtually for 2.5 hours each and once face-to-face in the final all-day session. At each meeting there were some plenary sessions (of the whole of one jury), but most deliberations took place in groups of about six with a facilitator. Each on-line session dealt with a different trade policy area, i.e.

- The impact of UK trade policy on the rest of the world

- Balancing trade between territories and sectors of the economy

- Privacy and international data transfer

- Food trade and the environment

CITP researchers made carefully-balanced, impartial presentations on aspects of these but then withdrew for the discussions. The face-to-face meeting had one session on each of the four issues based around a specific question, plus an introduction and a wrap-up session. Face-to-face the format was for NatCen to present on an issue, for deliberations to occur and then a vote to be held on which participants briefly recorded the main reason for their vote and then discussed how they voted. We then modified the scenario a little and the process was repeated. The modification approach was designed to reveal the jurors’ trade-offs more clearly. Details of the process are laid out in detail in the documents at CITP (2023).

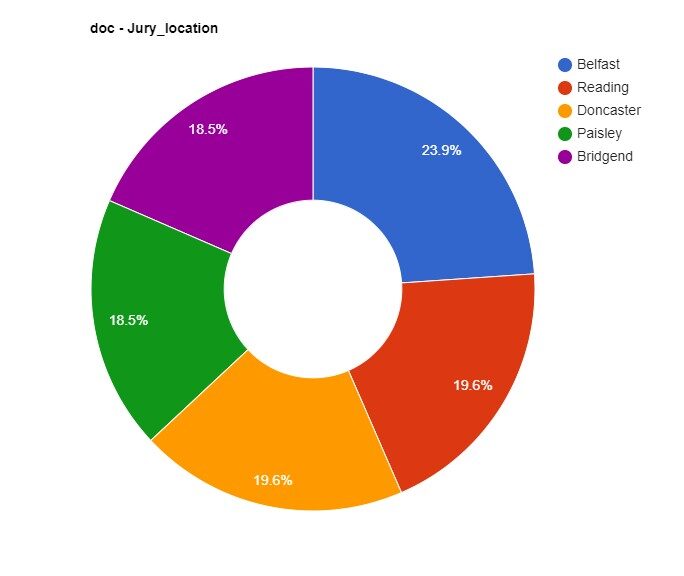

The overall CJs dataset (corpus) consists of 317,974 words and 396,380 tokens (token are words plus punctuation). Of these tokens, 139,527 (35.2%) were produced by male jurors, 157,972 (39.9%) by female jurors and the remainder (24.9%) to facilitators. Thus, the overall data is relatively well-balanced in terms of gender (it was perfectly gender-balanced in terms of membership.). Across the five locations, the distribution of tokens is also relatively even. The highest number of tokens come from Belfast (23.9% of total tokens in the corpus) while the joint fewest come from Bridgend and Paisley (18.5%), see Figure 1.

The final note in this section outlines transcription and presentation conventions of the data and addresses some of the challenges faced by working with natural spoken conversations. Quotations used in the paper are accompanied by the gender of the speaker and the location of the CJ (it is often not possible to identify the individual speaking in large groups). Where more than one juror is quoted, we refer to this as ‘various (speakers), [location]’. Where speech is produced by a facilitator this is represented in italic font. While the facilitator text is not the subject of our analysis, it often provides important context in which the discourses of the jurors can be interpreted. It is important to note that given that in spoken interactional discourse, such as the CJs, much of the meaning being expressed is extra-linguistic and, therefore, is not captured through transcription. There are also many examples of incomplete utterances as well as anaphoric references for which the anaphor is not clear. We include examples that we feel are relatively high in clarity and are not especially difficult for the reader to parse.

3. Results

3.1 The lack of trust

- I can’t trust anyone (Female, Bridgend)

- I don’t trust anybody, to be honest (Female, Reading)

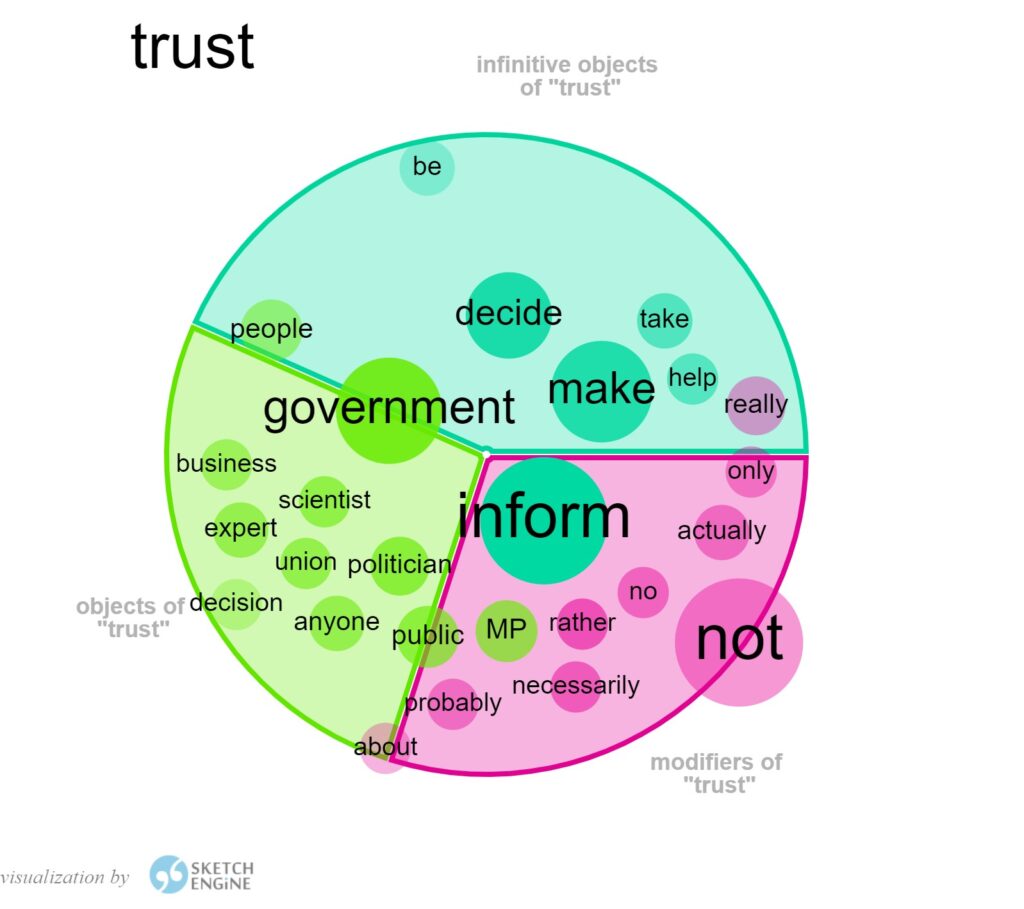

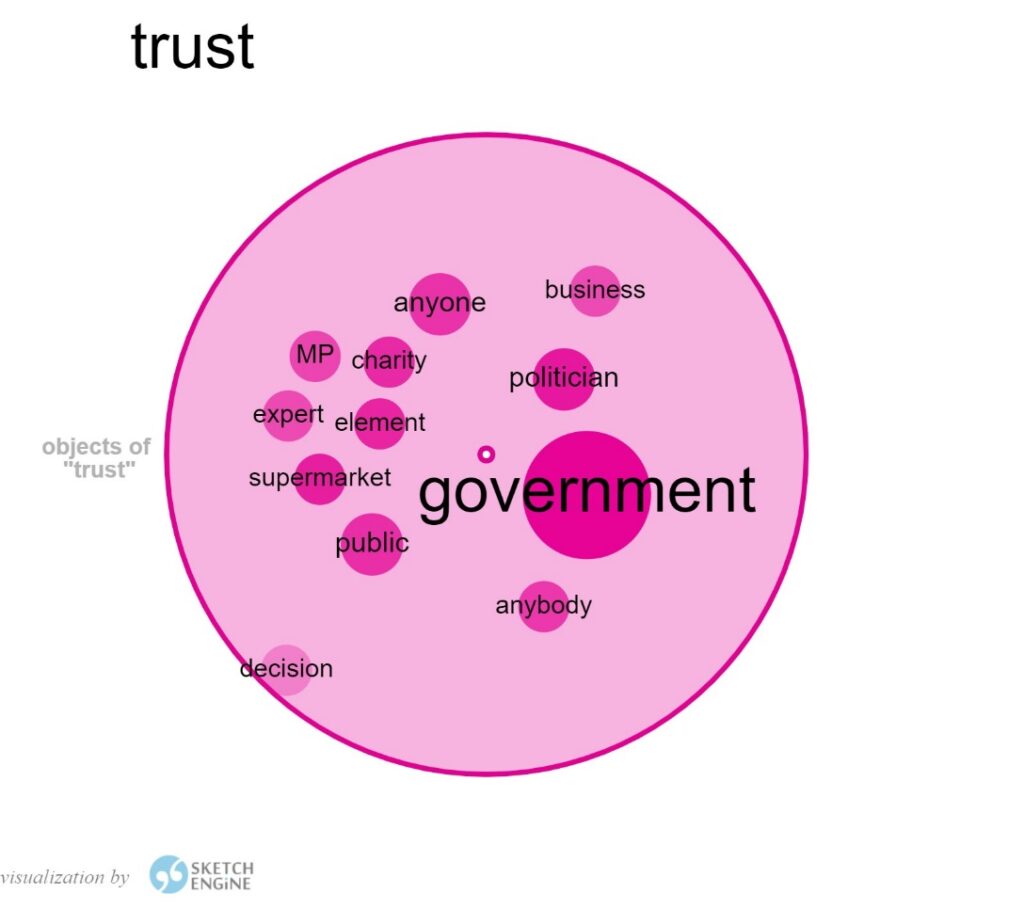

However, this lack of trust is not uniform, and there are some groups of people and institutions who feature in the context of not + trust more than others. This is evidenced by the grammatical objects of the not + trust construction presented in Figure 3.

This lack of trust is principally directed at political actors seen in the collocations between not + trust and government (n=14); politician (n=2); MP (n=1). For example:

- Who do I trust to inform? Well, I don’t trust the government […]They are what they call the public school mentality, isn’t it? They haven’t got a clue really. (Female, Bridgend)

- I don’t trust any of them, to be honest. We can go back to the: I don’t trust politicians full stop – which is sad that I feel that. Aye. (Female, Paisley)

- I don’t trust the MPs to [negotiate trade deals] because they will have a vested interest. (Male, Belfast)

The examples above exemplify some of the CJs’ attitudes pertaining to the government. For example, ‘[the government] haven’t a clue really’ reveals a negative affective stance towards the government and their perceived capabilities. Strong epistemic stances (see Section 2) are also demonstrated through the lack of hedging, e.g. ‘I think’, ‘maybe’, or ‘sort of’, while unhedged comments, such as ‘I don’t trust politicians full stop’, reveal a strongly held belief.

Despite this lack of trust in political actors, a number of jurors do comment that they reluctantly trust the government. That is, many have resigned themselves to trust the government in the perceived absence of an alternative:

- I have no choice but to trust the government. We were going to say, like, politicians, it’s like a bad word these days, but we’ve no option but to trust the government in international trade committees, that they’re speaking to people and know what they’re talking about. (Male, Belfast)

- Would I trust local government? They’re the only place you can go to. They’ve got more connection, the local government. Yes. It’s almost like choosing your form of execution, isn’t it …? Yes. What do you want to do; electric chair or a bullet? (Various speakers, Bridgend)

It is often unclear from CJs’ conversations whether it is political actors who are untrustworthy in principle or if it is the specific political actors of the day that are being objected to. While the lack of trust in these actors is evident, many jurors resign themselves to the necessity of politicians in the context of trade deals and that there are few alternatives so their trust towards these political actors is given begrudgingly.

3.2 Experts

The actors who are seen more favourably by CJs in the context of trade deals are experts. A number of collocations between trust and expert occur (see Figure 2). As expert is a semantically broad term, we unpack what/who the jurors refer to when they speak of experts. This can be identified by the behaviour profile for expert, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 displays the verbs used with expert as the grammatical object, nouns modified by expert, the modifiers of expert, and the nouns in conjunction with expert. Collectively these serve to highlight the sorts of domains of expertise that jurors referred to. In particular, academic roles collocate strongly with expert e.g. researcher (as both a modifier of expert and in conjunction with expert), university, and the related term scientist (as both a noun modified by expert and in conjunction with expert). Other specific fields such as business, medical, legal, and economist are also mentioned. Additionally, the more generic subject expert is mentioned as well as appropriate and relevant, that is, an expert in whatever is related to the specifics of a particular deal.

The trust afforded by CJs to these experts is clearly expressed, e.g.:

- trust the experts of the trades, so example agriculture would be farmers and so on. (Female, Bridgend)

- We really trust the scientists on this question [of food standards] (Female, Paisley)

While the examples above highlight the industries that jurors associate with experts in the context of trade deals (e.g. medical, legal), other collocates in Figure 4 speak to the types of traits that are associated with experts, particularly the modifiers independent and neutral which are qualities that the jurors valued. For example:

- [I trust] neutral experts [to inform trade policy] […] I said the other MPs, so Labour, Conservative, whatever, with the vested interest and baggage and maybe backhanders, whereas experts, we hope are above that (Male, Paisley)

The independence that the jurors associated with experts was also associated with international bodies, for example:

- Someone like the World Health Organization has a blanket view of what’s good and what’s not as opposed to us deciding that. You’re saying the WHO because they’re independent. Yes, they should be. Or an equivalent independent body. (Various, Reading)

These examples highlight a positive affective stance towards independent international bodies and their perceived capacity to prioritise the public good, rather than particular interests.

Close reading of sentences containing terms for experts and terms which are typically used in conjunction with terms for experts (see Figure 4) also reveals a similarly positive affective stance in terms of advocating for the role of experts in trade strategy, in particular in the context of the perceived elevated knowledge base of experts, relative to politicians, e.g.:

- It’s like the experts, the ones that are not in it for financial gain […] so they’re the knowledge. An MP might not necessarily have the knowledge. (Female, Doncaster)

- Let the scientists meet and agree the best decision. (Male, Belfast)

Jurors also mention that the government would be trusted to a greater extent if it was clear that they had consulted experts:

- Like we’d have more confidence if we knew that they [the government]’ve spoken to the experts in the field or spoken to whoever we felt should be relevant (Female, Reading)

Thus, for some jurors, the trust in experts can serve to offset their lack of trust in the government.

Trade unions, or their representatives, are sometimes framed as a specific type of expert who should be consulted on trade deals, although not without dissenters. For example:

- I’d also trust trade unions to have a part in it, because they obviously act on behalf of their members who are the general public. (Female, Belfast)

- I think maybe a trade union, they will think for their own interest so I am not sure about the union. (Female, Bridgend)

Another way in which we identify general sentiment is by analysing the verbs that occur in the context of a given noun (see, e.g. Biber 2006). For example, through the analysis of the verbs that are used with expert, we can provide additional insight into how the jurors perceive experts (see Figure 4). The strongest collocate of verbs with expert as object is need. This highlights the ways in which the consultation of experts is framed as imperative:

- We need experts who are qualified to comment on world population, world growth, who is dying of hunger (Male, Paisley)

- We need experts to decide whether this is […] worth the risk (Male, Paisley)

Ultimately, of all of the groups discussed in relation to trade deals, jurors frame experts most positively. They expressed trust in experts in the context of informing the government. In particular, jurors favour experts due to their perceived independence and epistemically leading position.

3.3 Public

Another group regularly discussed in the context of trust was the public (see Figure 2). The perception of the public in relation to trust is complex. On the one hand, CJs see the public as incapable of having sufficient knowledge to be trusted around policy decisions, for example:

- You don’t want to trust the general public to make the decision because we’re not informed enough, or we don’t know enough about it to be able to make an informed decision. (Female, Belfast)

- We are slightly more informed, but the rest of the general public would probably know very little (Female, Belfast)

Such attitudes, which speak to the perception of the limited epistemic position of the public, are also evident in the behavioural profile for the noun public (see Figure 5).

The collocates of public, such as idiot, child, and stupid (see Figure 5) exemplify the public’s perceived naivety and lack of knowledge:

- So we put business owners from the specialist sector, and then we originally had public, and then we agreed that the public are idiots (Female, Paisley)

- Don’t ask the public. The public are stupid (Female, Bridgend)

While the collocates educate and inform do occur in Figure 5, these are typically used in phrases in which they are negated, highlighting the way that the public are not educated or informed, with respect to trade strategy. For example:

- Are most of the public educated enough to make decisions like this? We’re not, are we, I don’t think (Male, Doncaster)

- I don’t think the public are informed enough to be involved in making big decisions like this. I think it needs to be left to the experts (Male, Belfast)

On the other hand, the public are conceptualised as being close(r) (adjective predicates in Figure 5) to relevant issues, and, as such, have a right to have a voice, for example:

- I was going to say, I don’t think many people trust the government, do they? Yes, I think also the people, the public are closer to the issues, have personal experience of issues that have affected them (Female, Belfast)

Many jurors highlight the value of consulting the public. However, as the CJs do not think that the public has sufficient knowledge of the intricacies of trade, they typically do not advocate for public involvement in making decisions that directly affect trade policy. This highlights a broader distinction between which actors were discussed in reference to those who were trusted to decide vs inform on trade policy.

3.4 Informing vs deciding

While attitudes towards different types of actors vary greatly, CJs also have a varied opinions on the sorts of responsibilities each type of actor should be tasked with. The jurors make a distinction between the actors that they feel should be involved in the consulting stage of trade deals and the process of decision making. This distinction is highlighted in the following example:

- So, yes, who else should inform? Who…? Yes, we kind of said that. We said the professors, the people who know what they’re talking about, the people who’ve studied this, and so we said they should make the decisions. We said they should inform. Inform, sorry, not make decisions. They’re the ones who should inform the government. Yes, so the decision-makers should be really listening to […] Because they’re the ones who inform researchers. It’s like the experts, the ones that are not in it for financial gain, the ones that gain something, so they’re the knowledge. An MP might not necessarily have the knowledge. Yes, they can make the decision, or they can put something forward, but they don’t know the knowledge. They’ve not studied it, so I think they have to listen to experts and researchers, people that know (Various, Doncaster)

Motivated by findings presented on Figure 2, we focus on the decision-making processes in relation to trade deals which are represented by a set of verbs inform/consult and decide (see Figure 2). We generate a visualisation of the collocates that occur as grammatical subjects of verbs to inform and to decide (Figure 6)9. Terms that appear closer to the left of Figure 6. collocate more strongly with to inform while those that appear on the right have a stronger collocation with to decide, while the size of the text relates to the raw frequency of the collocation (e.g. people has a higher raw frequency than Ireland).

Figure 6 shows that scientist and farmers, which are types of experts, are discussed in the context of informing trade policy. Relatedly, Figure 7 presents a comparative behavioural profile for decide and consult, which is near-synonymous to inform. It shows that public and people, as well as expert collocate more strongly with consult than decide. Thus, the semantic fields of the public and experts are more strongly collocated with inform/consult.

The theme of government is much more strongly associated with decide, such as MP, government, and minister (see Figure 6). Further analysis of the concordances demonstrates the ways in which the jurors framed (members of) the government as those who should be making decisions:

- Also we’ve come out with the UK Government making the decision about any trade agreement. Are they still the best placed to do this, or are there other groups that you think should decide on an agreement like this? I think so. I think that’s what they’re there for, isn’t it; they’re the ones that make the decisions but they need to make informed decisions. (Female, Reading)

- Yes, I think that was the point you were making earlier on; that that’s their job and that’s what they should be getting on with. Yes. … I would hope it’s – nobody else should be making decisions. Governments, they are elected and they can be dealing with it. Yes, because it’s the diplomatic system we have. I would just hope – my hope would be that their decisions are informed by consulting experts; that’s what we were discussing. (Male, Belfast)

One comment suggests that the government should simply enact the decisions of the public and experts:

- Who do you think you trust most to make these decisions? I don’t think one; I think it should be a combination of the public and the government. Yes. With the government initially with the public on a scale of, I reckon, about 70-30 per cent, so the public should be able to make 70 per cent of the choices, with 30 per cent coming from the experts – not the government – and then the government enforcing the decision. (Various speakers, Bridgend)

Jurors suggest that while experts should play an important role in the process, it is the role of government to ultimately make decisions:

- So, who do people feel like should be making these decisions about which jobs we might be creating, who should be winning or losing from trade? I think it should be the government – like we discussed in the last […] but with people feeding in, whether it be unions or the agricultural […] What do they have? Do they have some sort of union? I don’t know. Feeding into them and giving them the information, but we can’t have different sets of people making different decisions. Yes. In relation to trade policy. It’d be all over the place. It’s got to be Central Government I think, making the decision. (Male, Bridgend)

- I think government should always be making the ultimate decision because they are elected to do so. On the advice of the experts. And us. A wee bit. Select few, yes. (Male, Belfast)

The collocations of decide vs inform highlight the distinct processes in the development of trade deals. CJs provide recommendations and have clear ideas on obligations of various actors through a repeated use of deontic need or should. While the public and experts are more likely to be discussed in the context of informing and consulting on trade deals, it is the government who should be ultimately responsible for making decisions. However, a number of jury members, particularly in Reading, were not content with this arrangement, highlighting a desire for an entirely new and bespoke assemblage of people to be responsible for trade deals.

4. Discussion

The CJ data speaks to the limited trust conferred on politicians and political processes. The government was not trusted in absolute terms but were begrudgingly trusted to be responsible for ultimately signing trade deals. Using Cairney & Wellstead’s (2021: 2) typology of trust, we can think of this as ‘trust as necessary to society’, that is, while the trust is not enthusiastically given to the government, it is perceived to be essential for the running of the state. However, the government are not trusted in terms of their reliability, competence, degree of selflessness, or shared identity or values (Cairney & Wellstead 2021).

Experts, despite frequent lack of specification as to who experts actually are, are evaluated positively according to a variety of Cairney & Wellstead’s (2021) trust categories. In particular, their input in informing trade deals was viewed as necessary to society. They were also evaluated positively in terms of competence, (relative) selflessness, reliability, and performance. There are no categories in relation to which experts were routinely explicitly negatively evaluated. Thus, while then then Secretary of State for Justice, Lord Chancellor, Michael Gove famously claimed that the public have ‘had enough of experts’, this is diametrically opposed to the evidence from the citizens’ juries as well as other sources such as Ipsos (2023). Overall, the epistemic trust for experts is high, that is, they are perceived to have accurate and relevant information that can serve to benefit the UK’s interests in trade deals.

Applying Cairney & Wellstead’s (2021) trust typology to the public, they are not valorised positively in terms of competence. In particular, they are not thought to have the specific knowledge base required for complex geopolitics and economic analysis. However, they are perceived more positively in terms of having shared identities or values and mutual self-interest. That is, they are perceived to be trustworthy in the sense of a willingness to do the right thing, though not necessarily have the competence to carry this out independently, without the involvement of the government and experts. This nuanced view of public involvement in decision making has also been seen in research looking at another complex decision-making area, health (Litva et al. 2002). Employing Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation, the responses typically call for a partnership, without extending this participation to delegated power or citizen control.

While participants did not provide detailed rationales for the lack of trust, some did mention Brexit as a contributory factor for their scepticism of government and perceived vested interests, e.g.:

- I can’t trust anyone. Recently, because of Brexit as well, the promises which were made… Promises, promises, promises. (Female, Bridgend)

- Brexit were a game-changer wasn’t it? It was, and I also feel very manipulated by Brexit, by the media. (Male, Doncaster)

As the need for UK-specific trade deals is a direct consequence of Brexit, the spectre of Brexit looms large in the CJs. However, the scenarios, presentations and notes for facilitators all sought not to avoid re-igniting Brexit controversies, partly to try to maintain a harmonious atmosphere but also because we wished to reach beyond Brexit to more fundamental building blocks of attitudes to international trade. Thus, the relative scarcity of ‘Brexit’ in these conversations is not an indication of its lack of salience.

Conversely, the levels of trust conferred on experts seems to have been boosted by their role in the Covid-19 pandemic:

- Bodies like the IMF, World Health Organization during COVID, those international organisations, when they don’t have a single country it’s just like, ‘I’ve got to get elected in the next three years’. These organisations are less relying on elections coming up to win; it’s just like a general benefit of people. (Male, Bridgend)

- Well, in COVID we relied on the experts. Yes. For daily briefings and everything, it was the experts you listened to. Yes, if an expert was like, do you know what? This would work out better for you’ and then the MPs is like ‘no, you’re wrong’, I’d be like […] I don’t believe in the government or MPs. (Various, Bridgend)

5. Conclusion

The over-arching finding from the corpus-assisted discourse analysis of the citizens’ juries is that trust pertaining to actors involved in trade deals is severely limited. In particular, the role of politicians was viewed least favourably, while more positive affective stances were apparent in the context of experts. The perceived lack of transparency, the suspicions about vested interests, and the general lack of awareness of the day-to-day life of the public and their wants and needs meant that the levels of trust afforded to political actors was limited. Trust in politicians has never been high (Clements and King 2023) but it is worth remembering that in early 2023, when the juries were held, the British public had noticed that Brexit was not the overt success that had been promised and that in the previous seven months one Prime Minister had resigned in disgrace and the next had precipitated such an economic crisis that she had to resign after just seven weeks. Thus, one might hope for a little more trust in future.

It is also important to recall that many jurors did, begrudgingly, want ultimate accountability for trade deals to rest with the government and so believe that the government should make final decisions on trade. Jurors believed widely that the public as well as experts should be informed, and in some cases consulted, about trade-policy issues. However, there was little enthusiasm for them to have a decisive role, not least because they felt insufficiently informed about such a complex issue. Their stated trust in experts of various kinds reinforces the latter view.

The Citizen Jurors’ views on trust suggest a considerable institutional deficit in the UK treatment of international trade policy, which is, after all, a major component of overall economic policy. Future governments should speak more frequently and more honestly about the questions of trade policy; they, along with the public and the media, need to accept that given the nature of the trade-offs involved almost no policy will command universal support. Rather, the trick needs to be that the country’s overall stance on trade delivers benefits to nearly everyone and that where it cannot, provisions are made to ease any burdens created. In concrete terms, partly in response to these Citizens’ Juries, the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy has advocated:

- greatly strengthening Parliamentary scrutiny of trade agreements and trade policy (Hestermeyer and Horne, 2024, Winters 2024)

- better engagement with the UK’s devolved administrations and their populations on trade (Petetin et al, 2023), and

- related to suggestions from some jurors, reforming the UK Board of Trade to provide independent expert analysis and advice on trade policy to the government, Parliament and the public (Henig & Winters 2024, Winters 2024).

Footnotes

- Small caps indicate the concept, that is, the idea of trust, and italics are used when referring to the word trust metalinguistically. ↩︎

- https://citp.ac.uk/ ↩︎

- https://natcen.ac.uk/centres/centre-for-deliberation ↩︎

- In total there were 90 transcript documents: 5 juries x 3 discussion groups x 6 discussions (4 scenarios plus intro and wrap-up). ↩︎

- We use the Spoken British National Corpus (2014, Love et al. 2017) as our reference corpus. This is a 10-million-word corpus represents spoken English in Britain. ↩︎

- This n-gram search does not distinguish between trust as a noun or a verb. ↩︎

- This contrasts with 0.0013% of the baseline corpus. ↩︎

- We focus on the verbal rather than the nominal form here for two reasons. The first reason is quantitative. There are nearly four times more tokens of the verbal form (375 against 103). Secondly, a collocation analysis of verbs enables clearer insight into who trust is being conferred on by the jurors, thus the verbal analysis is more felicitous in order to understand the application of trust in the CJs. ↩︎

- In Sketch Engine, it is not possible to search for both inform and consult simultaneously in comparison with decide, thus we need to conduct the relevant searches sequentially. ↩︎

- The decide side of the figure refers to both government and Government: the former is generic while the latter refers to a specific government (almost always the UK’s). ↩︎

- Winters (2020) contrasts the official attitudes towards expertise in Brexit and Covid-19 policymaking. ↩︎

References

Angelou, Angelos., Stella Ladi, Dimitra Panagiotatou, & Vasiliki Tsagkroni. 2023. Paths to trust: Explaining citizens’ trust to experts and evidence-informed policymaking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration, Advance Online Publication.

Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), 216-224.

Biber, Douglas. 2006. Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 5, 97–116.

Cairney, Paul. & Adam Wellstead. 2021. Covid-19: Effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians and the public. Policy Design and Practice, 4 (1), 1–14.

CITP (2023) Research into public attitudes to trade, CITP, University of Sussex, https://citp.ac.uk/public-attitudes-to-trade

Clements, Michael and Laura King 2023. Trust in politicians reaches its lowest score in 40 years, IPSOS, 14th December 2023, https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/ipsos-trust-in-professions-veracity-index-2023

Dommett, Katharine. & Warren Pearce. 2019. What do we know about public attitudes towards experts? Reviewing survey data in the United Kingdom and European Union. Public Understanding of Science, 28 (6), 669-678.

Du Bois, John W. 2007. The stance triangle. In Robert Englebretson (Ed.), Stancetaking in Discourse, 139–182. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Eckert, Penelope. 2019. The limits of social meaning: Social indexicality, variation, and the cline of interiority. Language, 95 (4), 751–776.

Gauthier, David. 1987. Morals by Agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henig, David and L Alan Winters (2024). ‘Restructuring the Board of Trade for the Twenty-first Century’. Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy Working Paper 014, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/restructuring-the-board-of-trade-for-the-twenty-first-century

Hestermeyer, Holger and Alex Horne. 2024. Treaty Scrutiny: The Role of Parliament in UK Trade Agreements, Briefing Paper 9, Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/treaty-scrutiny-the-role-of-parliament-in-uk-trade-agreements

Jaffe, Alexandra. (Ed.). 2009. Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kiesling, Scott F. 2009. Style as stance. In Alexandra Jaffe (Ed.), Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, 171–194. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kiesling, Scott F. 2022. Stance and stancetaking. Annual Review of Linguistics, 8, 409-426.

Kilgarriff, Adam., Pavel Rychlý, Pavel Smrž, David Tugwell. 2004. The Sketch Engine. Proceedings of the 11th EURALEX International Congress, 105-116.

Kilgarriff, Adam., Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý, and Vít Suchomel. 2014. The Sketch Engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1: 7-36.

Litva, Andrea., Joanna Coast, Jenny Donovan, John Eyles, Michael Shepherd, Jo Tacchi, Julia Abelson, Kieran Morgan. 2002. ‘The public is too subjective’: public involvement at different levels of health-care decision making. Soc Sci Med, 54(12), 1825-37.

Love, Robbie., Claire Dembry, Andrew Hardie, Vaclav Brezina, & Tony McEnery. 2017. The Spoken BNC2014: Designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22(3), 319-344.

Locke, John. 1960. Two Treatises of Government. Ed. Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Partington, Alan. 2004. Corpora and discourse: A most congruous beast. In Alan Partington, John Morley, and Louann Haarman (eds.), Corpora and Discourse, Bern: Peter Lang, 9-18.

Petetin, Ludivine., Charles Whitmore, and Aileen Burmeister (2023) ‘Addressing barriers for Welsh institutions and civil society to contribute to UK trade policy’, CITP Briefing Paper 6, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/addressing-barriers-for-welsh-institutions-and-civil-society-to-contribute-to-uk-trade-policy

Winsvold, Marte., Atle Haugsgjerd, Jo Sagile, & Signe Bock Segaard. 2024. What makes people trust or distrust politicians? Insights from open-ended survey questions. West European Politics, 47 (4),759–783.

Winters, L. Alan (2020) ‘Brexit and Covid: Experts – who needs ‘em?’, The UK in a Changing Europe, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexit-and-covid-experts-who-needs-em/

Winters, L Alan (2024) ‘How do we make trade policy in Britain? How should we?’ Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy Working Paper 011, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/how-do-we-make-trade-policy-in-britain-how-should-we

About Us

We identify conceptual patterns and change in human thought through a combination of distant text reading and corpus linguistics techniques.