Conceptual variation: Gendered differences in the lexicalisation of the concept of COMMODITY in environmental narratives

by Justyna A. Robinson, Rhys J. Sandow, Albertus Andito

Abstract

Within studies of lexical meaning, conceptual variation has received little attention, possibly due to methodological difficulties with operationalising concepts. In the current paper, we build on the approach developed by Robinson & Weeds (2022) to study gendered variation in the lexicalization of concepts in environmentally-themed directives from the Mass Observation Project. We broadly define a concept as a cluster of (near-)synonymous and hyponymic terms representing a shared meaning. Previous research (Robinson & Weeds 2022) shows that gendered variation exists in collocational patterns of concepts. In the current paper, we focus on the varied ways in which a concept is lexicalized by men and women. A case-study of the concept of commodity shows that taxonomic differences between genders exist, with women using more specific terms to a greater extent than men. We suggest that the socially-variable articulation of concepts represents differences in speakers’ attention afforded to given commodities represented by the concept of commodity.

Keywords: conceptual variation, keyconcept, keysense, lexis, lexicalisation, sociolinguistics, gender, Mass Observation Project

1. Introduction

There is a spectrum of methodological approaches to lexical variation that vary according to the degree of control that the researcher has over the lexical usage in the data that they work with. At one end of the spectrum where control is highest, researchers use elicitation tasks, including surveys (for example, Britain et al. this volume; Robinson 2010, 2012). Lexical variation can also be attested through semi-structured interviews (for example, Braber, this volume; Bucholtz 2012). At the other end of the spectrum, there are data which had been produced with no agency of researchers, such as newspaper articles, radio recordings. Such work typically engages with methods of Corpus Linguistics (for example, see Wilson this volume).

The development of Corpus Linguistics has allowed for investigating another layer of lexical variation, i.e. variation in meaning between texts more broadly as opposed to the formal onomasiological variation that relies on functional equivalence between variants. This is typically achieved through a keyword analysis (for example, see Baker 2004). Such analysis involves profiling a target dataset against a baseline and identifying those words (or phrases) that are distinctive of the target data. Keyword analysis offers a powerful approach in identifying the ‘aboutness’ (Kilgarriff 2009) of texts in a bottom-up fashion. However, this method profiles word forms, not their meanings. Subsequently, it is up to a researcher to conduct a post hoc, and often ad hoc, interpretation of the meanings from a keyword list in search for meaningful themes in the text.

Previous research shows that the distribution of conceptual themes in the language used by gender groups is not homogenous. Based on text samples from 70 studies the United States, New Zealand, and England, Newman et al. (2008: 219–20) found that compared to women, men were more likely to talk about sports, money, occupation and less likely to talk about home, family, and friends. For a more detailed discussion of language and gender, including the related differences in socialisation practices, see Eckert & McConnell-Ginet (2013). Robinson & Weeds (2022) also discovered the existence of variation in concepts used by male and female witnesses in courtrooms as well as differences in conceptual collocation patterns across genders. In the current research, we ask if the gendered language also varies in terms of conceptual taxonymy. More specifically, we consider if men and women lexicalize concepts differently, that is, whether they engage with specific or general levels of a conceptual hierarchy, i.e. hyponymy vs. hypernymy, to differing extents.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we contextualise the current study within the growing body of work on concepts and lexicalization. Next, we explain the methodological approach that enables a conceptual analysis. Then, we turn to the dataset, which is the Mass Observation Recycling and Environmentalism (MORE) corpus. It consists of responses to three ‘directives’ on the topic of environmentalism collected by the Mass Observation Project. The analysis profiles the concepts within the dataset, including variation between men and women, using the concept of commodity (specifically commodity.n.01) as a case study. The choice of environmental narratives and the concept of commodity is motivated by the desire to understand better the characteristics of populations’ language and thinking in this economically- and socially-important area. We show the ways in which such a conceptual perspective highlights gender-based differences in behavioural practices such as that women engage with more concepts that pertain to domestic labour. We also identify variation in the lexicalization of concepts, with women typically using more specific (hyponymic) levels of the conceptual hierarchy than men. The analysis benefits from a range of visualisation tools. We conclude by advocating for the value of conceptual analysis and the opportunities it affords for lexical variation research. We note that this research is exploratory and serves as a proof-of-concept approach to the analysis of socially-variable patterns in lexicalization of concepts.

2. The Concept and Lexicalization

The last decade has seen an increased focus on concept-led linguistic research. One area that has led investigations into concepts is language change. A body of conceptual research has built on established historical thesauri, such the Bilingual Thesaurus of Everyday Life in Medieval England (BTh, Sylvester et al. 2017) or the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (HT, Kay et al. 2023), or on large corpora as in the Linguistic DNA project (Fitzmaurice et al. 2017).

A departure from this view of concepts is presented by the Linguistic DNA project which sees concepts as discursive clusters. According to Fitzmaurice et al. (2017: 25) “In any particular historical moment, a concept might not be encapsulated in any single word, phrase or construction; instead it will be observable only via a complete set of words, phrases or constructions in syntagmatic or paradigmatic relations to each other in discourse”. A discursive concept is made up of paradigmatic terms which habitually co-occur in language across large proximity windows. For example, Mehl (2022) shows that the discursive concept diversity-opinion-religion is made up of terms diversity, opinion, religion habitually co-occurring around 5000 times in EEBO-TCP. In other words, a frequent and mathematically significant occurrence of the trio diversity-opinion-religion indicates a possibility of an existence of an idea that was expressed by these three nouns in conjunction rather than by an individual term. Close reading of extracts representing the discursive concept allows for tracing the formulation of ideas regardless of whether they ever become encapsulated in a single term.

Language change research also pursues questions of modifications of different levels of conceptual hierarchy that happen as an outcome of language contact. Sylvester et al. (2022) show that terms making up conceptual categories get reorganised when distinct communities come to contact. In research querying the absorption of French-origin borrowings into Middle English, Sylvester et al. (2020: 28) show that these borrowings tended to enter hypernymic (more general) levels of conceptual categories. Surprisingly, these French tended to occupy semantic spaces where there was more, not less, lexical choice. In research exploring the obsolescence, Vogelsanger (2024: 24) finds that most lexical loss happens also at hypernymic levels as “the more specific the concept, the fewer words and senses we find, but in turn they seem to be more resilient, since they show much lower rates of obsolescence”.

A significant area of study focuses on lexicalization of concepts. While lexicalization generally refers to “the assignment of lexeme to a meaning” (Murphy 2010: 16), historical linguists tend to focus on various aspects of this process. Thus, Trousdale (2008) asks how once closed-class words or phrases develop lexical meaning. Alexander (2018) or Dallachy (2024) investigate how words that map new concepts are added to a language’s lexicon. Sylvester and Tiddeman (2024) develop measures of density of lexicalization. These studies show potential for using a conceptual view on language as a way making exploring social cognition, with lexicalization being a measure of “cultural attention” (Alexander 2018, Dallachy 2024) and a “function of speakers’ needs” (Sylvester et al. 2020: 28).

The approach to concept and lexicalization pursued in the current work can broadly be categorised in the tradition of the aforementioned thesauri-based approaches in that we consider a term’s usage, its sense, as a base for a concept. We also consider the concept as belonging to a network of hierarchically-structured meanings, i.e. structured horizontally in terms of (near-)synonymy and co-hyponymy and vertically in terms of hyponymy and hypernymy. We use WordNet (Fellbaum 1998), specifically WordNet 3 (Princeton University 2010), to profile senses and model the conceptual structure including semantic relations. WordNet has the advantage in this respect as it is made up of twenty hierarchical levels (Mohamed & Oussalah 2014), as opposed to, for example, the seven levels of the Historical Thesaurus (Piao et al. 2017), thus it enables greater granularity of analysis when it comes to researching hierarchical semantic relations.

3. Data

Senses and concepts become key if they occur frequently enough in a target corpus in comparison to a reference corpus. The choice of a reference corpus depends on a rage of criteria (cf. Baker 2004). In the current research the reference corpus comes from data collected by the MOP. As well as the directives, the MOP also issues calls for ‘Day diaries’ on the 12th of May each year since 2010. These diaries include descriptions of daily activities, thoughts that the writer has throughout the day, and generally provide an insight into the life of the diarists. The digitally-submitted responses to these diaries from 2010–2019 form the baseline with 4,101,605 words, from 3,070 diary entries (see Robinson et al. 2023).

🔍 Hover to Zoom

4. Method

In the current research, Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) is employed to determine which sense is the most appropriate for each word in the data based on the word’s context. We use SupWSD (for more detail, including an evaluation of its accuracy, see Papandrea et al., 2017), a WSD tool that uses a machine learning algorithm, i.e. Support Vector Machine, and WordNet (Fellbaum 1998, WordNet 3.0 (2010)) as the sense inventory, taking into account part-of-speech, surrounding words, and local collocations.

After each word in the corpora has been tagged by the appropriate sense, we perform analyses of the corpus through a bespoke Application Programming Interface. In order to identify differences in the usage of a senses or in the use of concepts between the target and reference corpora we use a measure of Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI, see for example, Huang et al. 2009, for a discussion of its application to conceptual analysis, see Robinson & Weeds 2022, Robinson et al. 2023). PMI enables the identification of keysenses and keyconcepts, i.e. senses or concepts which appear in the corpus more often than one would expect, given their frequency in a reference corpus. The higher the PMI, the more distinctive the sense or the concept of the target dataset relative to the reference corpus. The PMI is established in the way presented in Equation 1, where A is a sense or concept, B is a target corpus, P(A|B) is the probability of encountering a sense A or a concept A given a target corpus B, and Pref(A) is the probability of a sense A or concept A in the reference corpus.

In Section 5.1, using the tools discussed here, we explore the semantics of the MORE corpus. More specifically, we provide an overview of the distinctive senses and distinctive concepts. In Section 5.2, we focus on the case study of the concept of commodity to answer questions pertaining to taxonomic differences in lexicalization patterns between men and women.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Semantics of the MORE corpus: Keysenses and keyconcepts

🔍 Hover to Zoom

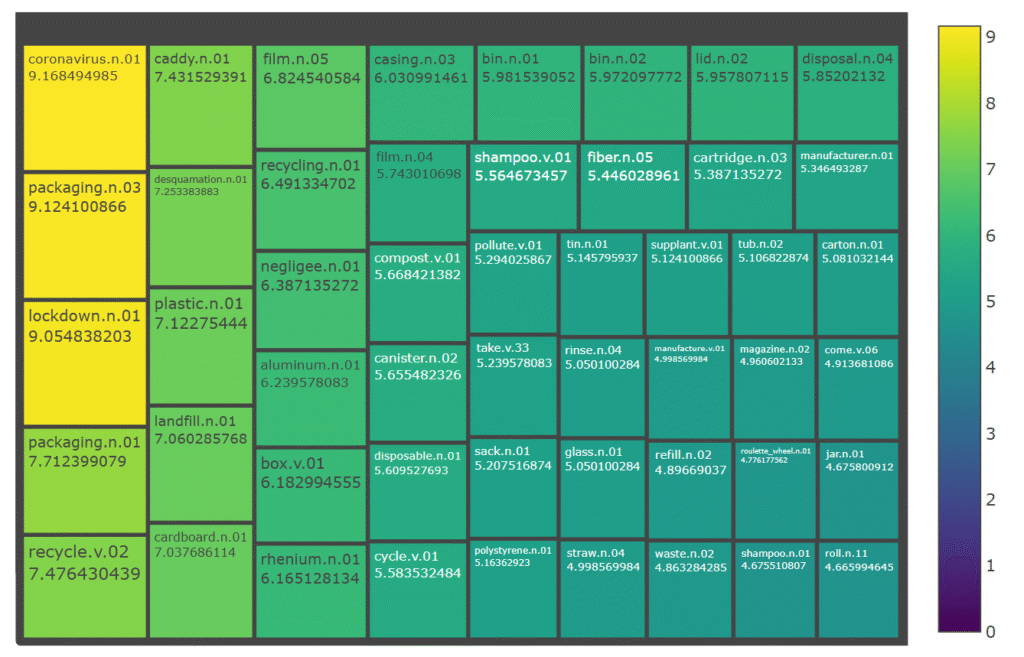

Figure 10.2 provides a semantic overview of the MORE corpus. The most distinctive sense of the corpus is coronavirus.n.01. This result occurs due to the very low frequency of this sense in the baseline corpus, coupled with its much higher frequency in the target corpus, particularly the ‘Household recycling’ directive, where the directive prompt specifically asked about the effect of Covid‑19 on recycling practices. Other senses provide a largely intuitive account of the content of the responses to the three directives, such as materials, for example, plastic.n.01, cardboard.n.01, and cellophane.n.01, as well as practices associated with environmentalism, such as recycle.v.02 and flatten.v.01.

🔍 Hover to Zoom

Given that the environmentally-themed directives make up the MORE corpus, it is not surprising that the respondents discuss types of containers and their uses, including innovative repurposing, as well as their recycling practices. However, not all daughter concepts of container.n.01 are highly distinctive. For example, bath.n.01 and boiler.n.01 occur less often than in the baseline. Other concepts with particularly high PMI values include use.n.01 (PMI=4.4), and its daughter concept recycling.n.01 (PMI=6.2), and waste.n.01(PMI=4.8) and its daughter concept rubbish.n.01 (PMI=3.3).

This current section illustrates an approach to semantic characterisation of data. The MORE corpus is semantically described from the perspective of senses and concepts. Figure 2 shows the most distinctive senses of the MORE corpus, including lockdown.n.01, pandemic.n.01, and plastic.s.02. The conceptual approach complements this by considering the taxonomic relation of hyponymy. For example, while a sense-level analysis highlights container.n.01 in the top 50 most distinctive senses, a conceptual analysis shows how not only is this sense distinctive of the corpus, but so are some of its hyponyms such as bin.n.01 and botte.n.01.

5.2. Gendered variation in the MORE corpus: Keyconcepts and lexicalization patterns

🔍 Hover to Zoom

🔍 Hover to Zoom

Relative to men, for women, the PMI of charity.n.01 is 1.4, husband.n.01 is 3.6, and home.n.01 is 1.3. Relative to women, for men the PMI of internet.n.01 is 1.2, alcohol.n.01 is 1.1, and wife.n.01 is 4.1 highlighting that men engage with these concepts to a greater extent than women do in the MORE corpus. Such results testify to heterogenous behaviours and practices across genders.

Even when concepts have similar overall rates of usage across demographic groups, their internal structure can also differ. This is exemplified through the concept of commodity.n.01 which is selected as a case study. This concept is used similarly by men and women in the dataset as measured by PMI. It is used very slightly more by women with a PMI=0.18, when compared with men. The raw frequency of usage is N=1021 for women, and N=445 for men. While the PMI for commodity.n.01 for both genders is similar, the internal structure of the concept displays a great deal of variation across the two gender groups. The conceptual profile for commodity.n.01 among female writers is presented in Figure 6, while the male equivalent is presented in Figure 7.

🔍 Hover to Zoom

🔍 Hover to Zoom

The conceptual profiles for males and females display a number of differences in the type of artifacts with which males and females interact. Numerous examples of gendered clothing items are distributed disproportionately across the gendered groups, with concepts such as dress.n.01 (PMI= 0.3), negligee.n.01 (PMI=0.9), brassiere.n.01 (PMI=1.7), and skirt.n.02 (PMI=0.1) displaying positive PMIs in the female data, and suit.n.01 (PMI=2.2) and jean.n.01 (PMI=1.8) displaying positive PMIs in the male data. There is also a greater attention paid to domestic labour evident in women in the conceptual profiles of commodity.n.01. For example, white_goods.n.01 is used more by women (PMI=0.8). Within the concept of white_goods.n.01, the female data has positive PMIs for refrigerator.n.01 (PMI=0.5), dishwasher.n.01 (PMI=2.0), and washer.n.01 (PMI=2.2), while the only hyponym with a positive PMI in the male data is cooler.n.01 (PMI=1.8). Similarly, laundry.n.01 has a positive PMI in the female data (PMI=1.1). There are also examples of the asymmetric distribution of childcare, with diaper.n.01 (PMI=2.8) having a positive PMI in the female data.

One surprising result is that shirt.n.01 is used more by the female observers (PMI=0.82), despite it being an artifact stereotypically associated with men. However, we can account for this result by identifying that many of these examples involve accounts of interactions with male clothing by women, such as Example (1):

- I reuse my husband’s cotton shirts in crafting. [Household recycling, female born in the 1960s]

The observed differences in conceptual profiles for males and females suggest that concepts provide a window into community behaviours. The artifacts represented by the concept of commodity and the asymmetric gender distribution with which they are engaged with, are a medium through which the physical world is experienced by men and women.

Another perspective in which the current research highlights gendered conceptual variation is through taxonomic differences, i.e. the levels of the conceptual hierarchy that men and women typically engage with. This differential engagement is evident in the fact that the sunburst in Figure 6 is noticeably ‘busier’ than the one in Figure 7. That is, the male data in Figure 6 includes more empty space, that not occupied by daughter nodes (hyponyms). Take clothing.n.01 as an example. Proportionally, men are more likely to use the more general level sense clothing.n.01, while women are more likely to conceptualise clothing with a greater degree of specificity. When the concept clothing.n.01 is used, men use the sense clothing.n.01 32.2% of the time, compared to 24.7% for women. Thus, women are more likely to use a hyponym. To illustrate this, example (2) is more typical of a male conceptualisation of clothing.n.01 at the more general category level, whereas the Example (3) is more typical of a female conceptualisation at a greater level of specificity (brassierre.n.01):

- Used batteries are taken to local supermarkets where they can be recycled, also clothing can be recycled at various points around the area. [Household Recycling, male born in the 1950s]

- I’d like to be able to recycle old bras [Household Recycling, female born in the 1950s]

The internal structural differences in concepts evidence variation in the ways men and women express those concepts by their use of words, that is, in the ways they lexicalize those concepts. In the analysis of commodity.n.01, differences arise in the levels within the conceptual hierarchy at which concepts are lexicalized, with men lexicalizing concepts at more generic levels, and women lexicalizing concepts at more specific levels.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This research presents a new approach to querying semantics of texts by engaging with horizontal ((near-)synonymous and co-hyponymic) and vertical (hyponymic and hypernymic) semantic relations. The current approach highlights hyponymy as a critical aspect of language variation alongside more widely-research relations in socio-semantics, such as synonymy and polysemy. Exploring texts through the lenses of keysense and keyconcept enables semantic content to be profiled which can empirically navigate further analysis and close reading. In one way, the concept-driven approach is more specific than more traditional alternatives, such as the keyword analysis, in that it distinguishes polysemous senses of the same word form. In another way, it is more general as in a conceptual approach, it is less relevant which (near-)synonym is used, what matters is the meaning expressed. This perspective enables the analysis to centre meaning, while variation in word form is secondary to this approach. We advocate for using the current conceptual approach that offers a bird’s-eye view of the text meaning with conjunction with close reading in order to develop the most robust insights into a text’s semantics (for example, Robinson et al. 2023).

The current research demonstrates the ways in which a conceptual perspective can tell stories of socially-asymmetric behavioural practices. Examples of this include the way in which the use of clothing items exhibit gendered patterns, such as brassiere.n.01 being used relatively more by women and suit.n.01 by men. Similarly, there is a higher frequency of concepts pertaining to domestic labour and childcare in the female data. Results that testify to heterogenous behaviours and practices across genders are corroborated by the parallels with other studies, such as those observing gender-based differences in the share of domestic duties (Bianchi et al. 2012; Thébaud et al. 2021). The parallels between such previous and the current research speak to the validity of this approach.

Another question to consider is why lexicalization would take place at different levels of the conceptual hierarchy for men and women. One possibility lies in the notion of cultural and social needs speakers express via lexicalisation practices (cf. Alexander, 2018, Dallachy 2024, Sylvester et al. 2020). Another possibility considers engaging with cognitive foundations of language and perception biases among men and women. At this stage, we suggest that the lexicalization of commodity.n.01 reflects the attention afforded to the artifacts with which men and women engage. The question of why the lexical representations of objects display differential attention across community could to be explored further via socio-cognitive research frameworks (Pütz et al. 2014).

To conclude, the proposed concept-led approach shows potential beyond a case of gendered variation. The current analysis could apply to any demographic category, including cross-sectional categories. It remains to be seen the extent to which the presented results hold for other concepts in a systematic way. Also, motivated by studies outlined in Section 2, such as Sylvester et al. (2020) or Vogelsanger (2024), further research could explore the relationship between lexicalization and different levels of the conceptual hierarchy in the context of language change. While it is argued elsewhere (for example, Sandow & Braber, this volume), that lexis can provide a lens into society, we argue here that a conceptual approach lends a particularly felicitous perspective to this endeavour. The proposed conceptual approach affords further methodological, theoretical, and applied opportunities in sociolinguistics and beyond.

Footnotes

- Acknowledgements: We would like to thank two anonymous Reviewers for their helpful comments on the earlier draft of this manuscript. We would like to thank the broader team at Concept Analytics Lab at the University of Sussex, particularly Julie Weeds, Willam Kearney, Yassir Laaouach, and Ray Davey for the work on the API that underpins the research presented here. Supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Impact Acceleration Account, at the University of Sussex (AH/X003531/1).↩︎

- Robinson & Weeds (2022) use the term characteristic concept.↩︎

- https://ht.ac.uk/classification/↩︎

- In the WordNet sense inventory, the refers to the nominal part-of-speech category. The 01 identifies this as the first sense of this form in WordNet. By way of example, person.n.01 is defined as ‘a human being’ and person.n.02 is defined as ‘a human body (usually including the clothing)’.↩︎

- Figure 1 does include these individuals, but as there are very few in number, they are not clearly visible.↩︎

- These are hypernyms from the perspective of cow.n.01, but hyponyms from the perspective of entity.n.01.↩︎

- For example, ‘The video I watched suggested that rice and pasta should be stored in reusable glass containers’ [‘Future of consumption’ directive, male born in the 1970s] and ‘some of the plastic containers are recyclable but I guess that several are single-use’ [‘You and plastics’ directive, female born in the 1930s].↩︎

- Concepts with a negative PMI also appear in Figure 3 and 4. In terms of the colour coding key on the figures, these are coloured as if their PMI value is 0.↩︎

- The highest levels in the conceptual hierarchy correspond to lowest numbers in the WordNet hierarchy. Thus, the highest levels are entity.n.01 at level 0, physical_entity.n.01 at level 1 and so forth.↩︎

- This task requires a modification of the PMI Equation (1) in terms of target and reference datasets.↩︎

- Beyond the concept of commodity.n.01, this effect holds for other concepts where men are more likely to use the broader sense and women are more likely to use a hyponym. For example, in the concept of child.n.02, men refer to the specific sense 53.6% of the time, compared to 40.7% for women; in chemical.n.01 the values are 3.9% for men, 1.9% for women, and in waste.n.01, the values are 76.9% for men and 71.2% for women. ↩︎

- We thank an anonymous Reviewer for this observation.↩︎

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj/eng, see especially Paragraph 2.↩︎

References

Alexander, Marc. 2018. Lexicalization Pressure. Plenary lecture delivered at 20th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, University of Edinburgh.

Baker, Paul. 2004. Querying keywords: Questions of difference, frequency, and sense in keyword analysis. Journal of English Linguistics, 32: 346-59.

Bianchi, Suzanne M., Liana C. Sayer, Melissa A. Milkie, & John P. Robinson. 2012. Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91: 55-63.

Bucholtz, Mary. 2012. Word Up: Social meanings of slang in California youth culture. In Leila Monaghan, Jane E. Goodman, & Jennifer Meta Robinson (eds.), A Cultural Approach to Interpersonal Communication: Essential Readings, 2nd ed, 274-97. Chichester: Wiley.

Dallachy, Fraser. 2024. A human-scale set of categories for the Historical Thesaurus of English. Dictionaries, 45: 145-68.

Eckert, Penelope. & Sally McConnell-Ginet. 2013. Language and Gender, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fellbaum, Christiane (ed.). 1998. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fitzmaurice, Susan. & Seth Mehl. 2022. Volatile concepts: Analysing discursive change through underspecification in co-occurrence quads. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 27: 428-50.

Fitzmaurice, Susan., Justyna A. Robinson, Marc Alexander, Iona C. Hine, Seth Mehl, & Fraser Dallachy. 2017. Linguistic DNA: Investigating conceptual change in Early Modern English Discourse. Studia Neophilologica, 89: 21–38.

Grondelaers, Stefan. & Dirk Geeraerts. 2003. Towards a pragmatic model of cognitive onomasiology. In Hubert Cuyckens , René Dirven and John R. Taylor (eds.), Cognitive Approaches to Lexical Semantics, 67-92. Berlin: Mouton.

Hoang, Hung H., Su N. Kim, and Min-Yen Kan. 2009. A re-examination of lexical association measures. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Multiword Expressions: Identification, Interpretation, Disambiguation and Applications, 31-9.

Kay, Christian., Marc Alexander, Fraser Dallachy, Jane Roberts, Michael Samuels, and Irené Wotherspoon (eds). 2023. The Historical Thesaurus of English (2nd edn., version 5.0). University of Glasgow. https://ht.ac.uk/. Accessed September 11, 2024.

Kilgrarriff, Adam. 2009. Simple maths for keywords. In Michaela Mahlberg, Victorina González-Díaz, & Catherine Smith (eds.), Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics Conference CL2009. Available at: https://www.sketchengine.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2009-Simple-maths-for-keywords.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Lakoff, Robin. 1973. Language and woman’s place. Language in Society, 2 (1), 45-80.

Mass Observation. 2010. Mass Observation Archive. Available online at: http://www.massobs.org.uk/. Accessed August 21, 2024.

Mehl, Seth. 2022. Discursive Quads: New Kinds of Lexical Co‐occurrence Data With Linguistic Concept Modelling. Transactions of the Philological Society, 120 (3), 474-88.

Mohamed, Muhidin. & M. Oussalah. 2014. A comparative study of conversion aided methods for WordNet sentence textual similarity. Proceedings of the AHA! Workshop on Information Discovery in Text, 37-42.

Murphy, Lynne M. 2010. Lexical Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newman, Matthew L., Carla J. Groom., Lori D. Handelman., & James W. Pennebaker. 2008. Gender differences in language use: An analysis of 14,000 text samples. Discourse Processes, 45: 211–36.

Papandrea, Simone., Alessandro Raganato, and Claudio D. Bovi. 2017. “SupWSD: a flexible toolkit for supervised word sense disambiguation,” in Proceedings of the 2017 EMNLP System Demonstrations, 103-8.

Piao, Scott., Fraser Dallachy, Alistair Brown, Jane Demmen, Steve Wattam, Phillip Durkin, James McCracken, Paul Rayson, & Marc Alexander. 2017. A time-sensitive historical thesaurus-based semantic tagger for deep semantic annotation. Computer Speech & Language, 46: 113–35.

Princeton University. 2010. About WordNet. Available at: https://wordnet.princeton.edu/. Accessed 10/12/2024.

Pütz, Martin, Reif, Monika, and Justyna A. Robinson (eds.). 2014. Cognitive Sociolinguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Robinson, Justyna A. 2010. Awesome insights into semantic variation. In Dirk Geeraerts, Gitte Kristiansen, & Yves Piersman (eds.), Advances in Cognitive Sociolinguistics, 85-109. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Robinson, Justyna A. 2012. A gay paper: Why should sociolinguistics bother with semantics? English Today, 28: 38-54.

Robinson, Justyna A. & Julie Weeds. 2022. Cognitive sociolinguistic variation in the Old Bailey Voices Corpus: The case for a new concept-led framework. Transactions of the Philological Society, 120, 399-426.

Robinson, Justyna A., Rhys J. Sandow, & Roberta Piazza. 2023. Introducing the keyconcept approach to the analysis of language: The case of regulation in Covid-19 diaries. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 6, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2023.1176283.

Sylvester, Louise., Imogen Marcus, & Richard Ingham. 2017. A bilingual thesaurus of everyday life in Medieval England: Some issues at the interface of semantics and lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography, 30: 309–21.

Sylvester, Louise., Megan Tiddeman, and Richard Ingham. 2020. An analysis of French borrowings at the hypernymic and hyponymic levels of Middle English. Lexis: Journal of English Lexicography, 16, doi: 10.4000/lexis.4841.

Sylvester, Louise, Megan Tiddeman, and Richard Ingham. 2022. Semantic Shift in Middle English: Farming and Trade as Test Cases. Transactions of the Philological Society, 120: 427–46.

Sylvester, Louise and Megan Tiddeman. 2024. Lexicalization, polysemy and loanwords in anger: A comparison with non-affective domains in Middle English”, Lexis 3, doi: https://doi.org/10.4000/12ize

Thaler, Richard H. and, Sunstein Cass R. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Thébaud, Sarah., Sabino Kornrich, & Leah Ruppanner. 2021. Good housekeeping, great expectations: Gender and housework norms. Sociological Methods & Research, 50: 1186-214.

Trousdale, Graeme. 2008. Constructions in grammaticalization and lexicalization: Evidence from the history of a composite predicate construction in English. In Graeme Trousdale & Nikolas Gisborne (eds.), Constructional Approaches to English Grammar, 33-67. Berlin: Mouton.

Vogelsanger, Johanna. 2024. Obsolescence and innovation in the Middle English religious lexicon. To appear in Transactions of the Philological Society. Advance Online Publication, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-968X.12310.

WordNet. 2010. WordNet 3.0. Available online at: http://wordnet.princeton.edu (accessed February 27, 2023).

About Us

We identify conceptual patterns and change in human thought through a combination of distant text reading and corpus linguistics techniques.